Boy, Reconstructed

How hypnotherapy successfully repairs damage inflicted by childhood trauma.

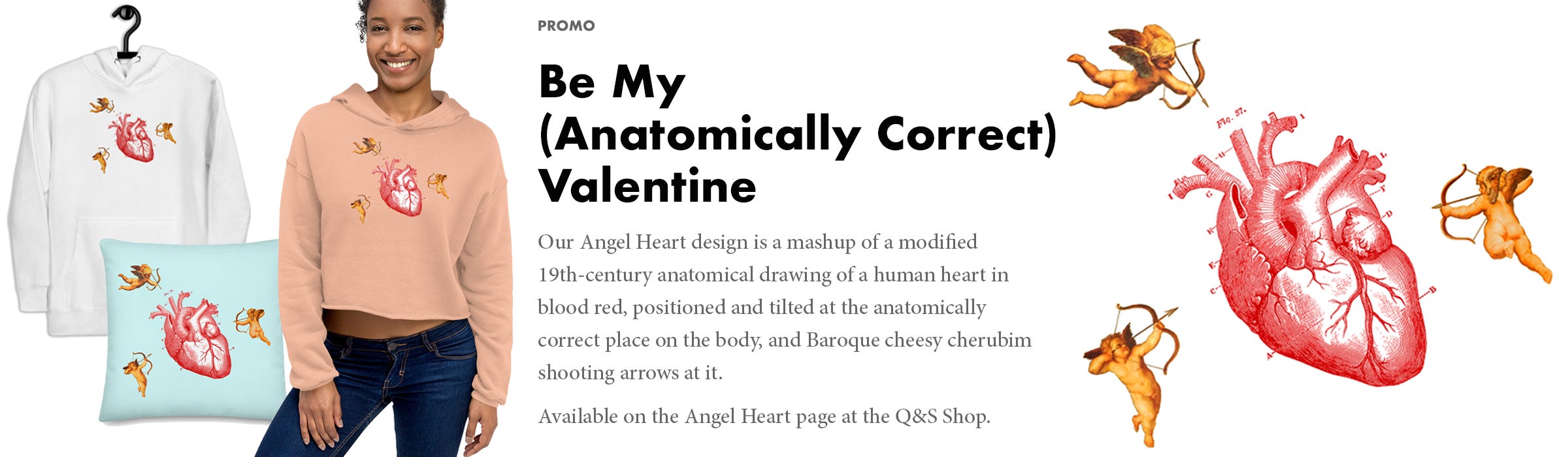

Quibblers & Scribblers is a reader-supported publication with an affiliated concept shop featuring my designs. Free subscribers get 10% off and free shipping of infinite items in a single order. Paid subscribers get 20% off and free shipping on infinite items in an infinite amount of orders. Bargain, eh?

Or bookmark this essay for later and go shopping instead — much more fun:

I think this piece might be standalone. Still, it’s probably wiser to read Part One, Boy, Interrupted, first.

RECAP:

After years of believing and living my family’s narrative that my failings in school were due to my general terribleness as a person, but suspecting in middle age that it might have been a learning disability, “maybe dyslexia,” I take a neuropsychological evaluation that reveals I’ve always had severe ADHD, masked by abnormal linguistic abilities. Over a weeklong mother-of-all therapy-breakthrough hangovers, neural pathways damaged by lifelong abuse begin to reset thanks to hypnotherapy sessions over the past year.

What follows is a postmortem with a closer examination of the culture that produces that sort of parenting — currently at the forefront of the social conversation thanks to Critical Social Justice and The Gilded Age — and an overview of how hypnotherapy works.

THE GOOD SHEPHERDS

An almost-unbelievably germane-to-this-series incident happened sometime in the beginning of 1999, when I was hiding out from the collapse of my second long-term relationship at the Hollywood offices of my first long-term relationship, Vivek Mathur, who owned an entertainment advertising agency that he started when he was twenty, during our lengthy, painful breakup.

We still spoke in the custom-made jargon that evolved early in our relationship, a mixture of Indian English and Bombay-inflected Hindustani slang that was heavy on the trilled Rs and needlessly long, mewling vowels punctuated by gossips-in-the-courtyard clucking. Karma Cola author Gita Mehta, Viking Penguin publisher Sonny's wife, astutely pegged it as “sounding like Parsi housewives.”

I was appraising comps for one-sheets Vivek and his team were creating for an upcoming awards-season release from Columbia Pictures.

“I that Winona Ryder?”

“Haan. Quite pagli-types, apparently,” Vivek replied, sharing an industry rumor that she was a crazy type.

“Achcha? I like her quite a bit, though. And this-thing with so much of lips and terrible wig?”

“Angelina Jolie, only.”

“Kon?”

“She was in Gia, the film about the lesbie supermodel heroin addict, died of AIDS. Won a Golden Globe for it, haan.”

“Achcha. I remember. Couldn’t watch. Bilkul flashbacks, only, too-too depressing. I remember her at the awards — astoundingly beautiful, I tell you. Looks like real tatti here.”

“They’re saying both will win awards for this, defi-types.”

Handwritten fonts are never my thing, but I focused on the title anyway. “Girl, Interrupted. More lesbie this-things?”

“Nah,” Vivek replied, a few tones more solemnly, prefaced by the emphasis of a clicking sound in the back right side of the mouth. “It’s about Kendra, only.”

I can feel myself then, physically taken aback, tilting away from the comps. There was only one Kendra, an ethereal, sylvan beauty I spent summers with at The Park, the Victorian summer colony overlooking the Hudson established by Knickerbockers like the van Rhijns in The Gilded Age.

Other than the clothing and shabby old cars instead of horses and buggies, little had changed about The Park’s culture. Harold Brodkey, dubbed “the American Proust” by New York Magazine, called us “crypto-genteel” in a snarling essay in The New Yorker, promising to write in more detail about our terribleness, but he never got around to it before he died. Perhaps he realized it would be too difficult to explain why he ended up buying a house in a bucolic, Anglo-American Episcopalian enclave hidden in a forest on the side of a mountain top, old-school New York City Yankee culture perfectly preserved, continuing as it had for centuries.

The fact he had a heavier lockjaw than any of ours, despite being Jewish and from Cincinnati, told me exactly why he wanted to be part of a formerly restricted country club. I asked him flat-out when I first met him what made him want to buy a house in The Park.

I didn’t add what I was thinking, for a change: That as Tina Brown’s darling, therefore the most precious character in the entire crypto-socialist New York literary world, a man who spent twenty-seven years working on his unreadable first novel, he was further from home than he realized.

“To house my collection of Americana,” he replied. “The house itself will be the jewel in the crown of the collection.”

He and his wife, Ellen, were gutting and renovating their entire cottage at enormous expense, an extravagance we’d hitherto never seen. Renovation for the pathologically shabby meant spray painting the wicker that came with the house — they were normally sold with the furniture, much of it the original owners’ from the late 1880s — and either slapping down a couple of coats of varnish on the floorboards yourself or by paying a Park kid to help, or sanding them a bit here and there and painting them in whatever color was on sale at the local hardware store, depending on what shape they were in.

Harold’s reasons were shockingly rude. Despite our sincerely down-to-earth demeanor, the most influential socio-cultural group the world has ever known has never had aspirations to be a life-size snow-globe diorama embedded in the living room wall of a consummate New York literary snob.

Still, Harold was right, just not in the way I think he meant: We were the ultimate representation of pure Americana. But we weren’t what he and, in my experience, most Americans outside our socio-cultural sphere imagine us to be; however, everyone is free to own their own private America, just not to represent us unfairly without a response. I’m done with turning the other cheek, Claudine.

As far as I know, Harold is the only other writer in the modern era who has written about The Park. Like me, he wrote obsessively about himself but never divulged its real name or exact location, no matter how much he came to loathe us. Perhaps he couldn’t go against the will of The Park’s ineffable spirit, either.

It’s a place of binding spells behind a wall of temporal distortion. After a day or two, you lose sense of time; one moment it’s Memorial Day and you’re airing out the cottage, the next it’s mid-October, and the hereditary Superintendent of The Park, himself a true Dutch Knickerbocker, is turning off the water and you’re closing up the house.

Mum has the same reaction every autumn. Sniffling and dabbing her eyes with a tissue she keeps tucked in the sleeve of her cardigan, she’ll utter specific words as a plea to The Park to allow her to return the following May: “I don’t know why I cry every time; I’m just so sad to be leaving!”

As someone who grew up there, I have a deep love for it, deeper still since my outrage at the defamatory theories of Critical Social Justice, which has turned our own philosophies and principles against us, forced me to take our culture apart and examine us as an ethnicity.

The fact he didn’t get that we were overtly genteel when he bought a house there speaks to how embarrassed we are by privilege; we hide it so well that we forget where it is, or that we had it in the first place.

It was Kendra who insisted one summer when we both cresting thirty that we were middle class. Whatever my European-learned demeanor, I hadn’t given my precise social rank any thought beyond a go-to statement, “To acknowledge that there is an aristocracy in America is un-American, therefore the most un-aristocratic thing an American can do.”

The idea of an upper class in this country was absurd, and for the most part still is; a considerable portion of my struggles with writing about it is trying to be less disingenuous, more realistic.

I believed almost everything Kendra said concerning the human mind and interpersonal dynamics. She flitted in and out of the human mind’s Underworld easily, at will, while I sat there on the banks of its Styx doodling in the sand, terrified and anxious, waiting for her return.

I’d been smitten with every part of her being since I was a boy: her lithe pixie body, small waist, broad shoulders, a gymnast’s physique; the wind-chime laughter; a full, generous mouth that rivaled Angelina’s; the untethered unpredictability that kept me on edge with dread that she’d vanish down an ancient, broken stone path in the forest and never come back; the irresistible allure of her bona fide, card-carrying insanity, with those “crenulated arms” from self-inflicted slash marks.

When I began therapy over seven years ago, I’d refer to myself now and then as “middle class.” Dr. Borkheim would nod politely and repeat, “So you think you’re middle class. Interesting.”

After four years of listening to my Park-ish lack of self-awareness when it came to my privilege — Yankees of my ilk are really that allergic to it, as much as we love it on Brits, Europeans, and Asians — he expelled a rare huff, adjusted himself in his modernist leather armchair and said, “You are not middle class.”

“Okay. Upper-middle class, then.”

“No. I’m upper-middle class.”

“Don’t you dare say it, Jamie.”

“There are only two places to go, Kendra. And we sure as fuck ain’t working class.”

“You’re such a snob.”

“Kendra, your father was an ambassador… Where’re you going?”

“Home. Call with my shrink.”

“Don’t be angry. Okay, okay… we’re middle class. But who cares?”

“I hate you.”

“Are you coming over for dinner?”

“No.”

“I’m making rosemary and garlic roast chicken.”

“Maybe. Maybe not. I don’t know.”

Down the ancient stone path she traipses, constantly on the balls of her feet — she might take flight at any moment. The Park’s jungle of hemlocks, pines, maples and birches scoop her into a protective embrace, reading me up and down scornfully, “How could you?”

She’s gone, maybe forever, maybe not. I don’t know.

“Kendra’s been sent away,” my mother said casually while chopping salad in the kitchen one day when I was in my late teens. “To some sort of hospital or institution, not sure. They say she was taking a lot of drugs and hanging out with a bad crowd in Cairo.”

Her father, a Nixon appointee to Hungary, had retired from the Diplomatic Service and was now president of the American University in Cairo; perhaps he was involved in the same extracurricular activities that Dad was in Italy — I don’t know why he wouldn’t have been, but it’s one thing to speculate about my father, another about Kendra’s. Per Wikipedia, her father grew the University into a formidable presence in the Middle East. What better cover than academia? Again, I speculate.

Robert De Niro’s spy drama The Good Shepherd with Matt Damon and Angelina Jolie is a reasonably accurate portrayal of my natal world, the sort of college secret societies that recruited my father, and summer enclaves warded by the shield of the Episcopal Church at the entrance like The Park.

I was overly fixated on the minutia when I saw the film. “Our women look nothing like Angelina Jolie.”

That’s not true: Kendra was easily as beautiful, as were other women I knew growing up; they simply didn’t wear all that makeup, even in the early Cold War era in which the film was set.

Now that I revisit stills via Google, that is indeed what I found distracting: Jolie’s styling and general L.A. persona are too Marilyn Monroe and obvious, not brittle and arch enough; not even Sidney Biddle Barrows, the Mayflower Madam, wore that sort of Bloomingdale’s makeover. Matt Damon is also over-groomed, too fussy and slick, Ralph Lauren’s take on us.

But I quibble, and our culture isn’t interesting enough for nuances. Plus, Americans know it by heart already; no matter how we’re idealized by outsiders like Ralph Lauren, or demonized by the Critical Social Justice activists we have foolishly nurtured — a lesson that Harvard, an institution that forms the bedrock of our culture, is paying for dearly — this country is the manifestation of our ideals and philosophies. We really do mean and live by what’s written in the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution and the Plinth of the Statue of Liberty. All of that is us.

Overall, The Good Shepherd is pretty spot-on. The image on below left could easily be the Fourth of July Dance at The Park clubhouse, right down to the Adirondack furniture. The one on the right, well, that’s one extravagant, expensive manicure for a Yankee gal — no doubt a Vassar grad.

When she returned to The Park and we reconnected in our mid-20s, Kendra regaled me with stories about her four years in “the Bin,” always with great humor, like she’d been living inside the haunted house ride at the funnest amusement park in the world, even when they restrained her for hours on end wrapped in ice-cold wet packs. We laughed especially hard at stuff like that. In her telling, the Bin was American Horror Story: Asylum as a broad comedy.

Girl, Interrupted captures some of the absurdity in Kendra’s stories, but she never allowed me to see the serious side of it. Maybe it’s because I was a kindred damaged spirit; with me, she could revisit the horror with the giddiness of a children’s game of Let’s Pretend because I traveled to those memories with her and…

I’m flattering myself. She was that way with everyone, a girl untethered.

She did grow sober once when we were in our early thirties. I was sliding deeper into depression; she helped as best she could, namely by introducing me to yoga and making sure I swam and hiked every day.

We were at the pool late one afternoon. The black dog was mauling my mind. We’d had a chuckle over an anecdote about the Bin when she said, “The only reason you got away with it, Jamie, is you’re a boy.”

When Mum came up for the weekend, I told her what Kendra had said. “What rubbish!” she snapped at the sacrilege of suggesting that her firstborn might have a disorder. “Why would you listen to her? She’s crazy.”

I’m perfect and brilliant, just the way she made me. The fact that I’m lazy, irresponsible, naughty, ungrateful, a profligate spendthrift who expects others to support him, and in recent years a liar when it comes to being honest with the next generation about the abuse I endured — only when they’ve asked me about it; all kids are fascinated by family histories, and ours is positively Lemony Snicket — is proof of what a terrible person I am, why I’ve always been Piggy the Scapegoated Black Sheep, to whom they’ve merely been good shepherds by meting out lifelong punishments and exilings.

The Ninth Circle of Hell is a tropical paradise compared to the cryogenic freezer of Anglo-American “tough love” parenting.

THE CONSTANT EXILE

My niece Savannah called me from The Park in late this past August, an unusual thing; we almost always communicate by text.

“Uncle James, I was at the pool and this woman came up and said, ‘You’re Jamie’s niece, aren’t you?’ It was Kendra.” Savannah’s voice, quivering between the shock and awe of having just had a genuine supernatural experience, made me chuckle-sigh with nostalgia.

I imagined Kendra — no doubt still lithe and athletic at 60, not a pound gained since our youth, more Galadriel now than the tomboy pixie of before — emerging like a zephyr from the forest behind our communal pool after purposefully climbing the ancient stone stairway from her house jutting from the cliff and supported by stilts, framing a view that kicked off the utopian Hudson River Valley School of painting, on the outside a seemingly modest, yellow-shingled structure cloaking the secret of the wainscotted living room’s thirty-foot cathedral ceilings like an expert illusionist.

“Oh, it’s a dream!” exclaims niece Marion as she sits in a rocker on the upper porch.

“Isn’t it, though?” sighs Aunt Ada, blissfully.

“It’s no longer fashionable, apparently,” sniffs Aunt Agnes. “But I’m not throwing more good money away trying to keep up with the Russells by building another cottage in Newport. We only just finished this!”

I base that imaginary scene from The Gilded Age on Aunt Agnes’ throwaway line about preferring Saratoga, located due north between The Park and Albany.

At the end of every summer, the founders of The Park helped their servants pack up their cottages for the winter and sent them on to New York to open the townhouse. Descending from their aeries in the funicular, they attended the Saratoga Meet horse races on Labor Day and returned by boat to the City for the beginning of the season.

“We talked for hours,” Savannah said with what-just-happened-to-me surprise. Raised in the strictest Indian tradition of never, ever uttering anything negative about the family’s internal business, her omertà proved no match for the open-sesame of Kendra’s exotic, grey-blue Scandi Mata Hari eyes and her disarming, unselfconscious charisma.

“I told her that you’re estranged from the family. She said, ‘Yeah, I probably would’ve done the same.’ Then she said, ‘You know you wouldn’t exist if it weren’t for Jamie.’”

She was referring to the fact I’d been a dutiful Indian older brother and matchmade my sister’s marriage to a close Kashmiri friend over the course of my own wedding in Delhi in 2001.

In a classic example of the family’s exilings, my sister repaid me by concocting a silly dispute and escalating it with baseless demonizations — “You don’t know what my brother’s really like” — to the point where the only reason I wasn’t disinvited to her wedding is because the groom’s side wouldn’t hear of it. She compromised by making me the only family member who was excluded from participating in the actual wedding ceremony, the dazzling culmination of a series of seven events held in an outdoor amphitheater at Neemrana Palace in Rajasthan, attended by nearly all of my social circle in India.

I’d been Piggy the Scapegoated Black Sheep for 37 years by that point. I knew something of the sort would happen before I decided to matchmake, I just didn’t know what would be used as the catalyst. I told my wife, Rohini, and a few of our closest friends when my sister’s engagement was announced that some tamasha or other would erupt. Being Indians and utterly taken by my sister’s gregarious lioness energy, they thought it was farfetched paranoia.

“You don’t know what my sister’s really like.”

A few months before the wedding, I drove up from L.A. to meet my father in San Francisco in a last-ditch attempt to diffuse things, to try to explain that this sort of Anglo brutality towards a family member, so well observed in Saltburn, was unthinkable in India, especially for such an inane reason. Only he could undo the warped perspective of me that he had fostered in my siblings.

“Dad, please, just this once…”

He sat there with his blinking doe-eyed wife on the deck of his house on a marina, listening with an immovable expression, part grimace, part smile, thanked me for coming, and showed me the door.

“I don’t suppose you’ll stay for dinner,” a formality phrased in a way to signal that I wasn’t meant take up the offer.

“That’s kind of you, but I have to get back to L.A. for work.” Work and education are sacred in Northeastern Protestant culture, a hall pass to get out of almost every social obligation. You have us to thank for that massive student debt for a pointless liberal arts degree that you couldn’t get anywhere without in a system we set up, as well as the expectation of a sixty-hour work week, two weeks’ vacation, and begrudging health insurance, if you can get it. You’re welcome.

I knew it was useless even before I drove up there; after all, he’d disinvited me to his own wedding for failing to repay a relatively small loan plus interest of 2% over prime by the agreed date. He was passively encouraging my sister; part of the reason I wanted to see him face-to-face was to make sure of that.

The reason for that particular exiling had happened two years before it, when we’d had our culture’s equivalent of a screaming, turn-the-tables, smash-the-plates fight on the patio of a restaurant in the West Village, he in a Brooks Brother’s suit, I in a Valentino: we growled at each other through increasingly clenched teeth, stood up abruptly in unison, nod-bowed to each other in crypto-royal-family style, and walked away in opposite directions.

I heard about his impending nuptials just before I returned from India. I went to Sundar Nagar in Delhi and bought them each a wedding present, his a silver elephant statuette as a nod to his obsessive devotion to the Republican Party. I wrote him a congratulatory note, saying I looked forward to the event.

He replied on an embossed Tiffany notecard with a line drawn across his name, “James Killough III,” per custom. It went something like,

Dear son,

Thank you for your letter.

After much consideration, I have decided I would like to be happy in life. You make me unhappy.

I’m sorry to say that we will be celebrating our union without you.

Love always,

Dad

I wrote him a scathing letter saying everything I’d always wanted to say but hadn’t, detailing the highlights of his abuses, and sent it with their presents.

I fell into his trap, as he knew I would: He used the letter as proof that my exiling was justified.

THE WICKED FAG PRINCE

“Growing up gay and having a learning disability must’ve been tough,” Dr. Borkheim said in our first session after my neuropsychological evaluation a few weeks ago.

Dad didn’t call me ‘gay’ — his preferred nouns were “fag/faggot,” which was typical at the time. Without going into too much detail about that aspect of the constant terror I grew up with, I didn’t realize until I began unpacking my childhood in the beginning years of my therapy work that I had been through so much torment about being gay/bisexual/whatever you want to call it.

Let me define my sexuality as (much) preferring sex with men, but having more platonic or nonsexual-romantic relationships with girls than with boys.

Until recently, kids who were abused because of their sexuality were usually runaways who had fled the dreaded Midwest — a place still held to be a threat to “at-risk trans kids” — to New York City for safety and acceptance. As a native New Yorker from the right side of Central Park, to paraphrase an opening scene of Oppenheimer, I had nothing in common with that; per the mindset established by my natal world centuries ago, my rare privilege canceled any struggle with abuse and the trauma that I endured after it became clear at around age four what kid of man I was destined to be.

“I don’t mind if you’re gay,” Mum quipped a year or two before I came out to her. “As long as I don’t have to march in that awful parade holding a sign saying, ‘I’m proud my son is gay.’” Mum was a decorator who worked with gay men daily.

It was my relationship with Vivek — we were getting a one-bedroom apartment together — that finally forced me to come out to her. I sat on a tufted ottoman upholstered with Clarence House fabric at the foot of her bed while she applied night cream to her elbows and arms. “We’ve always known,” she said. “What do you think it was like for us?”

The reality is that my experience was no different from those at-risk runaways from the Midwest, just set in a gilded cage with more restrictions on my behavior; the thousands of unseen protocols and behaviors that are pounded into you from the moment you say your first word — “No, not ‘Mama.’ We’re not Italian Catholics. We say ‘Mother, repeat, Mo-ther….’ — pull you through life like a marionette if you allow them — most of us do.

And let’s be honest, for once: Running away to New York, or even L.A. or San Francisco, is still the equivalent of joining the circus, the most fun you can have when you’re young if you can endure the hardships.

The reason I’ve kept a thread about privilege going is it was a third handicap in addition to the learning disability and my sexuality. My father, and to a lesser extent the rest of my family, despised and mocked my adoption of European aristocratic behaviors. It drove Dad, who loathed casteism and privilege with all his formidable Yankee might, so crazy he would get drunk and assault me every Christmas Eve, pummeling me with his rage about my unseemly flagrant privilege.

In my defense:

a) I went to a British grade school in Rome, where I learned a different performance of masculinity than Dad’s just to fit in. My sister and I spoke with RP accents during the school year, which we would ditch over a few days at the beginning of the summer at The Park.

b) People who speak other languages so fluently they could be locals unconsciously know that when you switch to that language, you adopt the mindset of the culture — it’s kinda freaky when you stop to think about it. I learned Italian from the Roman upper class I went to school with.

c) For instance, my first best friend in Rome when I was six was Prince Jonathan “Jonty” Doria-Pamphilj, who also turned out gay. His mother would pick us up from school in a blue Rolls Royce for playdates at the palazzo. This is where we played hide-and-seek:

Can you blame me for being a bit of a snob when I was younger and still working it all out?

As for my learning disability, it wasn’t just my abnormal linguistic abilities that covered it up, it was the projection of aspirations on the firstborn and my father’s namesake that made him, and to a lesser extent Mum, blind to it.

Side note: My pushback to the anti-privilege culture of the Northeastern Protestant Establishment would be my embarrassment about the numeral after my name, growing up not just amidst titled nobility, but within walking distance of the world’s only remaining absolute monarchy, the Holy See.

I don’t correct my mother when she boasts, “James was the first in his class to read.” The truth is I was second-to-last. I remember because it’s marked in my selectively pristine neurodivergent’s memory bank as being a trauma: I pulled myself together at the last moment, passed the test for reading the alphabet, and was rewarded with that first book only because I was determined not to be last.

The same goes for her follow-up line, “He was reading the [International] Herald Tribune/Time Magazine when he was eight.” The truth is I was looking at the pictures and trying to make sense of the comics.

I was taken for a second psychological evaluation when I was around seven to try to make sense of why such a blazingly intelligent child was failing at school. In the second half of the British equivalent of Grade 5, it was determined that I was so smart that I was bored. I was put in Grade 6 for the rest of the year, which was an even worse disaster.

By Grade 8, I developed full-blown Oppositional Defiant Disorder in response to the Lazy Fag Prince torment and stopped attending school altogether. I’d get off the bus and wander the fields of the suburb of Rome where the British school was located most of the day, only attending drama class, eating lunch, and hanging out with much older friends at recess.

I was removed from school and tutored for the second half of Grade 8, which is when I was finally able to learn at my own pace. Namely, I was taught American English and Hemingway-style creative writing by a tutor who had previously taught at Groton, one of the best prep schools in all Yankeeshire. That refinement of my linguistic abilities allowed me to fake it as best I could at St. Stephen’s, the American prep school I was to attend the following year, and then at Trinity School in New York.

The culture of exiling me from the family began the weekend my brother was born. I was suddenly sent away on an Italian Boy Scout trip for the weekend, even though I wasn’t a Scout. My mother had deliberately conceived another male child using the Shettles Method with the objective of having “the spare” replace the heir and distract Dad from his constant abuse.

After that, I was sent away for the beginning of each summer to the Lido del Sole YMCA beach camp on the Sardinian coast, which was a kids’ Lord of the Flies hippy paradise.

Following my first semester at St. Stephen’s, the exilings grew: I was literally thrown out of the house and put in boarding at the school, even though my family lived across town, half an hour away in Roman traffic. Because of my abysmal report card that first semester, I was excluded from the family Easter safari in Kenya. I spent those two weeks by myself in the school dorms, reading graffiti about “James the fag” in the boy’s toilet stalls.

I don’t know how I graduated Trinity; I imagine an arrangement was made, just as I knew earlier than early decision that I was admitted to Wesleyan, even though I didn’t have anything like the grades or scores to be admitted — I was a third-generation legacy and Dad was an actively involved alum.

My freshman year, I directed two plays, rarely went to class, and wrote perhaps a couple of gibberish papers. I’d reached my majority and was finally able to declare my freedom from the torture of the rickety, patchwork Victorian education system by dropping out and moving to Paris to become a creative professional.

Per my conversations with ChatGPT, I chose the right kind of profession for the limitations of my brain. I need to reverse myself from a statement I made in an essay published prior to the neuropsych eval when I echoed my family’s orthodoxy that if I’d stayed in school and within my natal world and taken the entry-level position at Morgan Stanley after a B.A. from Wesleyan and an MBA at Harvard, I’d be worth $100 million today, sitting comfortably by the fire at the Union Club, where the Duke of Buckingham stayed in the finale of season two of The Gilded Age.

That was never an option for a boy interrupted by a neurodivergent brain like mine.

Furthermore, how do you look at the cursory overview of my academic struggles that I’ve just written and not understand as sophisticated New York parents that your child has a learning disorder? That’s rhetorical: they knew, it’s just that it was unacceptable, as was my sexuality and European-style outward manifestation of the truth about our rare privilege.

YOU’RE GETTING SLEEPIER AND SLEEPIER

The first phase of my therapy lasted about six years. Dr. Borkheim guided me toward unburdening myself of most of my crippling low self-esteem, depression and anxiety through standard psychotherapy, which I pursued with the devotion I gave to the first seven years of my Sufi practice.

I’m still working out a more precise understanding of the mechanics of why I achieved such remarkable results with psychotherapy given the severity of the abuse I endured and the resulting trauma, especially compared to most of my friends.

I believe it’s somehow related to my neurodivergence giving me the ability to see social narratives that neurotypical people take as being as real as being pure constructs no different from the fictions I create as a writer. I base that on observations to reactions like the one to this newsletter’s tagline, “rewriting fictions that drive the world,” which has proven to be something most neurotypicals don’t seem to grasp.

I thought they would right away, especially after the lashings of reductive doctrines from critical theory over the past decade. From my atypical view, all that’s done is layer more fictional religious doctrine on top of what it claimed it wanted to destroy when Harvard set it loose on the world at the turn of the century.

Once the effects of my PTSD were under control, but still not completely gone, Dr. Borkheim shifted our work to the second phase: hypnotherapy to repair the damage the abuse caused by misaligning the neural pathways in my brain. The purpose has been to reconnect those pathways to a healthier, more typical format by revisiting traumatic events as well as their residual emotions in a hypnotic state.

As someone who perceives social narratives, performativities, all three forms of religions — spiritual, social, systemic — and other constructs as being no different from Narnia and Middle Earth, it’s safe to assume that I would’ve been the most skeptical person possible about the efficacy of hypnosis. That was certainly true prior to the most significant turning point in my therapy, when I’d made such meaningful progress that I stopped drinking heavily without realizing I’d done it.

Before that, whenever the word “hypnosis” popped into my frame of reference, I imagined the sequence in The Adventures of Tintin: The Seven Crystal Balls, when a Sikh mesmerist hypnotizes Madame Yamilah, a panel from which is the lead image of this section.

After the miracles that we achieved in the first phase of my therapy, I trust Dr. Borkheim more than anyone I’ve ever known to guide me in the right direction. I willing to try hypnosis, open to giving my skepticism the boot from my mind’s control room.

The initial phase is known as Ideal Parent Figure Protocol. After guiding my mind into a semi-conscious state, session by session we built an alternate-reality world, with the equivalent of the Welcome Area in online virtual world games like Second Life or The Sims.

From there, we created my Ideal Parents (IPs), an amalgam of mothers and fathers I admired and wished were my parents from The Park and the liberal, artsy faction of the American expat community in Rome.

Once my relationship with my IPs reached a certain maturity and could be summoned at will when I was in a hypnotic state, we began to revisit traumatic experiences and emotions and use my IPs to reset my emotional reactions to them.

At some point in the process of graduating from that development phase, I triggered what I call a “mind event,” more commonly known as a “spiritual experience.” My Sufi meditation practice, zikr, connected to this new subconscious world, creating an internal safe space that has become a landing area beyond the welcome area. I’ve dubbed it “Nirvana.”

Without elaborating too much, I believe I’ve finally understood experientially why the Hindu representation of enlightenment is the third eye, and above all why the greatest Sufi masters — Rumi, Avicenna, and Abu Bakr — are considered to be the earliest practitioners of psychotherapy. Zikr is hypnotherapy designed to stop the all-important nafs — ego-consciousness — from scratching itself raw, to borrow David Mitchell’s line about the purpose of books.

Psychology is a common profession for modern dervishes. My first Master of the Path was once head of the Department of Psychiatry at Tehran University.

Months later, IPs aren’t the only tools that we’ve developed to use in repairing misaligned neural pathways. I won’t go into greater detail because hypnotherapy, like all spiritual paths, is experiential and differs from person to person.

What I want to convey is that it’s so effective that I intend to become an advocate for it. If you are in any degree of psychic pain, I urge you to try it, to trust it, and to stick it out. To paraphrase what they say in 12-Step Programs, it works if you allow it to work.

A series of events led to my estrangement from the adults in my family in 2019. The first was at my stepmother’s eightieth birthday in 2018. Dad and I spent a couple of hours together trying to have a private conversation in the kitchen, one of those useless attempts to reconcile a man who didn’t remember what he did to his gay-neurodivergent-overtly privileged firstborn and namesake because he was a blackout alcoholic.

Whereas I remembered all of it like it happened yesterday. I will never forget, never stop ruminating about it, but my emotional reactions aren’t nearly as painful and wrathful.

Later in the living room, with the entire family assembled, in his most sententious Republican Establishment voice, like he was kicking off a prayer meeting in Washington, out of nowhere Dad addressed the spare-now-heir, “Hunt, you were probably too young to remember when we were at Treetops in Kenya…”

It was both fascinating and horrifying: By bringing up my first great exiling from the family, he was subliminally reminding them of who I was, how I was meant to be treated. He probably didn’t even know he was doing it, just as they weren’t aware of why they did it. The problem is, they won’t stop.

Such is the power of narratives and characterizations, of the fictions that drive families, societies, countries, the world.

After his wife’s sudden death a year later, I visited Dad in Texas. He was living in an area where people like me are still far from accepted; when I tried to make a reservation for the memorial at a local BnB, the owner made it quite clear that I wasn’t welcome.

Despite over 40 years in AA, sponsoring all those people, Dad never apologized to the person he wronged the most, the one still struggling and coping with the effects of his abuse and the culture of exiling me that he instilled in my siblings, which Mum has also taken up, now that my once-excellent long-term memory has become a pack of inconvenient truths that she has taken to calling “lies.”

A few months after their despicable behavior over my birthday weekend at The Park in 2019, I sent a couple of texts to my siblings as passive tests of their state of mind about me. When I had confirmation of my suspicions, I realized that it was hopeless, that this would never end, that I wanted to live the last third of my life in relative happiness, and that didn’t include them.

Dad passed away over Thanksgiving in 2021. My niece Savannah told me after he was gone. I felt nothing, no emotion, not even relief.

As for being so public and forthright about what my family has done, and continues to do passively with the way they’ve chosen to handle my estrangement, Anglo-American tough love works both ways. Framing them, their words and actions with my writing, and displaying it for all to read is the only means at my disposal to try to make them see what they’ve done.

It’s not too late to change a narrative until it is.

I was having lunch in Hollywood with my nieces seven or eight years ago. They were still struggling to reconcile what they were being told about me by my sister and parents with their experience of me — it wasn’t adding up.

“But, Uncle James, why do they say you’re lying?”

“Well… what sort of a person makes up lies about his sweet, loving, supportive family who have put up with all of his terribleness his whole life?”

“An evil one!” they chimed together.

I thought it was adorable, seriously — just writing that made me smile and expel little laugh-snorts through my nose. Kendra would’ve found it hilarious, I’m sure of it.

My certainty pulls back the curtain on us lying on the shaggy-soft lawn in front of Mum’s house — which Dad and I ripped from the forest, top-soiled, and seeded by hand the summer I turned fourteen — repeating “An evil one!” in little-girl’s voices, chortling harder with each repetition till ribs pop,

our joy trumpeting, twiddling its nose at

ice-cold wet-packs and exile > reset > exile

as it’s whisked away on

waves of wind tussling treetops,

tumbling down, Alice, down, down,

tripping under the bridge and over the falls,

swooping across the much-painted Cove —

onward and onward and onward —

galloping the Valley like the Headless Horseman,

thundering: “Forward ho!” till all Yankeeshire

raises its arms in relieved surrender

to a girl and a boy,

interrupted, reconstructed.

Thanks for reading.

Part Three of this four-part series begins to unpack the role of divergent thinking in the creative process.

REMINDER: Even if you’re both a bit stirred and shaken by what you’ve just read, I’m assuming you got this far because you didn’t hate it. Please scroll down (or up) and tap the little heart button. Thanks!

Quibblers & Scribblers is a reader-supported publication with an affiliated concept shop featuring my designs. Free subscribers get 10% off and free shipping of infinite items in a single order. Paid subscribers get 20% off and free shipping on infinite items in an infinite amount of orders. Bargain, eh?

Link to the concept store:

FURTHER READING:

'The Crown': Taking the Fun Out of Funerals

Written over the days before the neuropsych eval, but published the day after. This contains the mis-imagined future I might have had if I'd done "the right thing" that was never really an option.

Will The Real Elio Perlman Please Stand Up? — Part One

In which I consolidate my thinking about being Piggy the Scapegoated Black Sheep.

My first cursory attempt in 2012 to understand my role in the family and what psychology had to say about it.