Will The Real Elio Perlman Please Stand Up? — Part One

Why 'Call Me By Your Name' might well be inspired by real people.

ALL THOSE DETAILS

I first heard about Call Me By Your Name in late August, 2016. I was driving to Malibu for a script meeting with one of the film’s producers, Howard Rosenman. This was only my second meeting with Howard. It’s an hour and a quarter drive in mild traffic from West Hollywood, a good amount of time for two voluble people to get to know each other better. Among film veterans that usually means trading tales from the trenches and name-dropping to establish our relationship to one another on the Venn diagram of the business.

We were winding along a serpentine stretch of Sunset Boulevard, just before Santa Ynez Lake and the Pacific Coast Highway junction, where you glimpse the ocean for the first time. The sinking sun had given up trying to smooth the few ripples on the Pacific; hazy light caressed the cactus green of the Temescal Canyon hills as they slumped into the ocean, buffed with fool’s gold and burnt sienna. The view has reminded me of Italy at each unveiling, every time I’ve driven out here, for meetings, for the beach, for romance.

“I just got back from a few weeks in Italy,” Howard said, perhaps reminded himself. “We were shooting a small film I produced, directed by Luca Guadagnino. Do you know him?”

“I do. Loved I Am Love.”

“He’s genius. Brilliant. I bought the rights to a book eleven years ago, Call Me By Your Name, by this Egyptian Jew, André Aciman — family had to flee Alexandria in the ‘sixties when Nasser threw all the Jews out. Have you read it?”

I hadn’t, but I’m only a good gay when it comes to the sex, not the culture and lifestyle. Otherwise, I’m what’s known as ‘non-scene.’

“When I first read it, it reminded me of this other Italian film from way back called Garden of the Finzi-Continis, about Italian Jews in World War II. Don’t know if you know it.”

“I do. Vittorio De Sica doing Luchino Visconti, almost as well. I grew up in Italy. Italian cinema inspired me to become a filmmaker.”

“Oh? Anyway, took me eleven years to make. Armie Hammer’s in it. James Ivory wrote the script. You must know who he is.”

“I love Jim. I tried to buy Merchant-Ivory a few years ago with backing from Indian billionaire investors. Pulled out at the last minute. Yeah, well.”

“Interesting. So, they just sent me a Vimeo link of Guadagnino’s cut with music, finished, everything. He did it in three weeks. Looks ready for release, can you believe it? I just saw it a few hours ago. I cried and cried…”

We were still almost a year from when I would experience “cried and cried” myself. In this moment, I dismissed the melodrama as Howard’s signature celebrity-infused, hyperbolic producer-patter, with inserts of snappy, diplomatic gossip.

Over the next few months, I followed the reviews as they trickled in from the festivals; they were breathless with affection. Call Me By Your Name did seem like The Finzi Continis meets Ivory’s secret-gay-romance classic Maurice. After the film exploded out of Sundance, it became clear that Howard’s chances of being nominated were excellent.

The next time we saw each other, in the summer of 2017, I said, “You realize you’re going to be nominated, Howard.”

“I dunno. Let’s see.”

A little over a month later, I began a romance with Wes. He was something of a gay ideal: a farmboy from Alberta who worked in construction. Tall, handsome, blond, hyper-masculine with an easy, jocular-jock charm that seduced everyone who met him. A type I’ve pursued since I was a teen. He was lying in my arms on our third date when I said, “I’ve waited a very long time for you.”

In mid-November of 2017, Howard invited me to a Variety screening of Call Me By Your Name at the Arclight in Hollywood. Wes and I had been a demi-couple for almost three months and were fast-tracking to a full couple sharing resources and laundry baskets out of expediency. A final Waterloo in his fractious marriage got him thrown out of the house by his husband. Moving in with me was an uncomplicated next step.

At the time of the screening, Wes knew little about me or my background; his struggles were many, mine few — a common dynamic in intergenerational relationships. He knew I was a native New Yorker raised in Europe, or an ‘Ameropean,’ a label I cribbed from the Grindr profile of an American raised in France. (It wasn’t a match.) I’d probably mentioned to Wes that I speak five languages, that I began my film career in India, that I was in therapy being treated, successfully, for PTSD-related depression resulting from childhood abuse.

Wes and I settled into our seats in row C at the Arclight Hollywood, the preferred spot for my six-foot-three, muscle-bear-daddy frame; there was at least ten feet between me and the front two rows. Those were reserved for Howard and the rest of the filmmaking team. There was to be a Q&A afterward.

The size of my quibbles about any film is usually in inverse proportion to its greatness. My quibbles about Call Me By Your Name were nanosized. I recognized the actor playing Elio, Timothée Chalamet, from another recent release, Ladybird. His French accent was as fluid and flawless as it needed to be for an Ameropean. He’s the real deal. That’s critical for me: I’ve long had issues with on-screen representations of my socio-cultural group. Still, I was unprepared for how Ameropeans might be portrayed during the era when I was a teenager in Italy.

True, Bernardo Bertolucci made a trio of films about American teens in Europe — The Dreamers, Stealing Beauty, Luna — but he didn’t nail it nearly as precisely as Guadagnino did. Bertolucci’s mannered filmmaking keeps me from connecting with my own world; it’s like watching a performance in a diorama in the Italian Wing of the Museum of European Oddities. Guadagnino’s social realism, however, authentically steeps viewers into the world of my formative years.

Around a third of the way into the film, my viewing experience veered onto a level of engagement that was entirely unfamiliar. Elio plonks himself down at the lunch table and joins a conversation in Italian about Oliver’s popularity. The way the name is pronounced in Italian — “awe-lee-veh-r,” with a short trilled R — connected what I was watching to memories of my own Oliver. As shock drained air from my chest, the cinema seemed to tilt forward. The rows where the filmmakers sat moved closer to the forefront of my awareness with extra crispness.

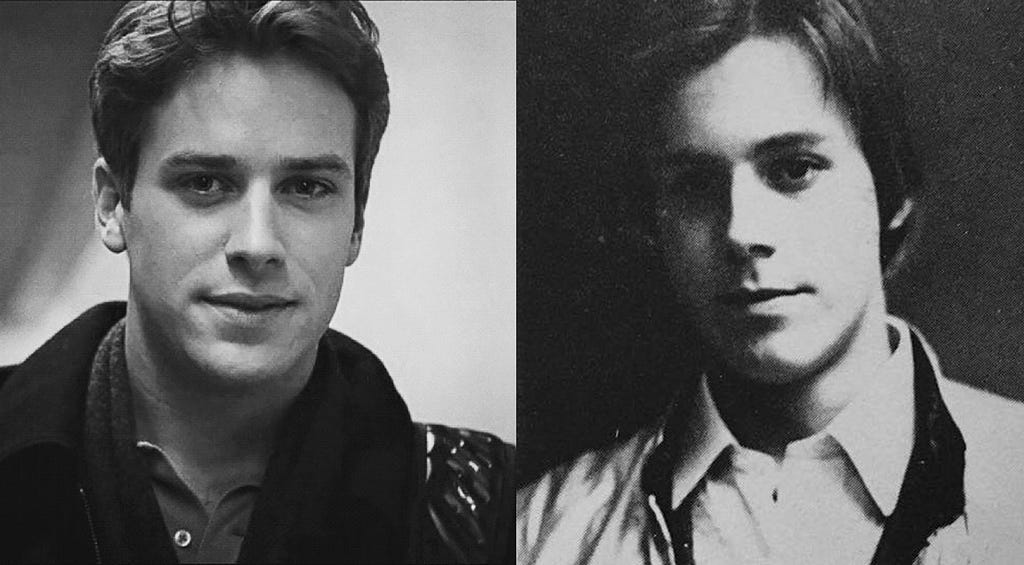

Temples pulsing, I automatically took note of the details, the way I would when I watched films I intend to critique. The film is set in the early 80s, around the time of my relationship with Oliver Ogden Stewart. Elio is two years younger than I was and behaves like I suppose I did: quirky, cerebral, passionate, impulsive. Chalamet also looked like me when I was his age and had more or less the same hair color and cut that I had at the time.

More jarringly, Armie Hammer was a dead ringer for how my Oliver would have looked in his early 30s. My professional experience registered immediately that no other “name” Hollywood actor, whose attachment could secure financing, was better suited to play him. At six-foot-four, my Oliver was an inch shy of Hammer’s height. They shared the same Ralph Lauren Polo ideal look: the long, square face with classically patrician features; the same hair quality (my Oliver was a few shades blonder); the Greyhound-lean, broad-shouldered body type; the ready smile and laugh of a person who’s had a reasonably happy childhood; a tall guy’s smooth gait, a confidence born from not feeling threatened by anyone.

Details like the lovers’ sexual fluidity, the polyglot friends, the summer villa, no longer seemed generic to the Ameropean experience in Italy, as they did in Bertolucci’s films. The kindly, intellectual parents — she Italian, he American — could well have been Jewish versions of Oliver Stewart’s parents, not mine. But as a screenwriter with more adaptations and fictionalizations filed away in the archives of dusty external drives than I can remember the titles of, I instinctively knew to overlook exact transliterations. As long as the essential elements of the story and interpersonal dynamics remain intact, it doesn’t matter which character, place or time embodies them.

When the third act kicked off — the last weekend in Bergamo — the crown of my head was a hotplate set to max. In the piazza, Hammer’s Oliver dances with some random girl and Elio pukes. As much disdain as I have for the anxious-puker trope, I knew that warp of terror weaving with a weft of grief, and there was nothing I could do to stop it. I was shoved back into the bathroom of Jules Feiffer’s apartment during my last weekend with Oliver Stewart in the summer of ’79. I was sixteen, in my underpants — no, his underpants — hugging my legs beside the exotic, impressively powerful pre-War toilet with no water reservoir, sobbing silently so he couldn’t hear me, so he wouldn’t start taunting, “Ma che c’hai, Ginsi? Dai! We’re in New York City, man! Just enjoy yourself!”

I choked up at the end of the film, but shock disarmed real tears. As chairs were set up below the screen for the Q&A with Guadagnino, Hammer, Chalamet and Michael Stuhlbarg, I began to formulate my response in Italian, just for Guadagnino, so the Americans wouldn’t understand. I was going to stand and gesture to the screen, “Ma quest’è la mia vita! Sono cresciuto così, io. Come cazzo hai saputo tanti dettagli?” This was my life. I was brought up like that. How the fuck did he know so many details?

All those details. Tutti quei dettagli. Tous ces détails.

Mercifully, I remained muzzled, restrained in my seat by the Italian discipline of bella/brutta figura — that two-clawed social vise, the beautiful and ugly face.

A Millennial in the audience questioned whether it was possible for Elio’s parents to be so understanding in that era. I resisted replying for the filmmakers that it was completely authentic. They were just like my Oliver’s parents, Luisa and Donald, albeit less glamorously haughty.

After the Q&A, I briefly introduced Wes to Howard, muttered congratulations, and reassured him that he was going to be nominated. My instincts were not to tag along with him and the other filmmakers — I couldn’t imagine not confronting Guadagnino. With false pep and cheer, I busied Wes into the crush of the exiting crowd.

As we were leaving the Arclight, Wes said, “That was moving, eh?”

“You don’t understand. That was my life — ” And out it crashed, raw emotion flooding the parking structure, wiping out many of the coping mechanisms that I’d developed to date in therapy.

For the next three hours, under the lemon tree in our garden, Wes watched a man he’d nicknamed ‘Beastie’ engage in a personal tug of war between a sobbing, heartsick teen, and my Lawrencian, hard-and-stoic Yankee soul. Wes smoked, his expression attentive while he absorbed the many fragments of my tangential storytelling. I finally explained why I said to him after sex on our third date, “I’ve waited a very long time for you.”

STUNG FERDINAND

My father was a hard-drinking advertising exec straight out of Mad Men. Mum was an ambitious Australian who escaped Melbourne when she was nineteen by hopping on a ship bound for New York, where she became secretary to the Chinese ambassador to the UN.

The marriage fell apart four years in, a decline that began after the birth of my younger sister. I was raised in a constant loop of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, a real-life manifestation of the son George and Martha pretended to have. I became the living receptacle of my parents’ rancor, a symbol of their misery and disappointment; a family scapegoat often embodies qualities that his parents loathe about themselves.

During the summer I turned four, Mum tried to springboard out of the marriage by having an affair with a married man from the neighboring country club. Dad blocked her exit by threatening to have her deported — she would never see her children again. If he couldn’t have her, nobody in America would.

Mum hadn’t yet obtained her U.S. citizenship. Dad was a former Army Intelligence officer, a member of the CIA-recruiting Skull and Crossbones secret society at Wesleyan. She knew that threats from men like him, at the height of the Cold War, were real and possible.

“That’s how much I love her,” he would sputter in my face when he was drunk and had assaulted me with no provocation, pinning me against the wall, the floor, the bed, or under the Christmas tree.

Dad was sitting in a board meeting at Compton one afternoon, depressed about the state of his marriage. “Then Milt Gossett said, ‘We’re having problems with the Italian offices.’ So, I raised my hand and said, ‘I’ll go.’” We were meant to go for two years. When the marriage didn’t improve to his satisfaction, Dad extended it to ten, equivalent to thirty adult years in a child’s development.

After a few months in Rome, my sister and I had learned all of the equivalent words in Italian that we knew in English. Given that our palates were not yet completely formed, our pronunciation was perfect. It still is.

I learned to read and write that first year at St. George’s English School. My favorite children’s book character was Ferdinand the Bull, a mighty creature that preferred to sit in the pasture smelling the flowers rather than butt heads with other bull calves desperate to unfurl their masculinity for all to see and cheer in the arena. Ferdinand is docile and loving, until he’s stung by a bee. He thrashes about the pasture wildly, stomping and snorting. It gets him mistaken for a normal corrida bull, thrown in the ring, and almost killed.

My Stung Ferdinand outbursts erupted more often as I tried to push back against the worsening terrors and injustices at home. When I was seven, Mum attempted to deflect Dad’s abuse by having another child, using the Shettles Technique of timing intercourse around ovulation to determine the sex. “I made sure it was a boy,” she told me repeatedly over the years, and wrote to the court in her divorce case, “so he’d be distracted and stop picking on you.”

If I identified with Ferdinand, my younger brother, born in Rome, was nicknamed the ‘Little White Bull’ from the moment he could crawl. He charged and crashed into everything around him; exactly the sort of boy Dad had ordered the first time around. Mum’s plan worked, partly; Dad was indeed distracted and happier. A couple of years later, we were allowed to return to the country house in Upstate New York for summers.

We were still under a sort of house arrest: picked up in June at JFK; driven up to the gated Victorian summer colony our house was in, an idyllic, therapeutically soporific village nestled atop a mountain overlooking Hudson, NY, a weathered shield of the Episcopal Church at an entrance so discreet you were unlikely to find if you didn’t know where it was; dropped off at JFK again at the beginning of September for TWA 800 back to Rome, via Paris.

What Mum hadn’t banked on was that I would become all the more irksome to Dad with the Little White Bull thundering around, reminding Dad of everything I wasn’t. As the mental and physical abuse intensified, so did my pushback. Still too weak to stand my ground physically against my father, I involuntarily sabotaged my own life by refusing to do homework, losing expensive gifts, and failing at St. George’s. By the end of seventh grade, I had all the symptoms of text-book Oppositional Defiant Disorder. I stopped going to school altogether.

St. George’s gave up on me at the start of eighth grade, just as they had with J. Paul Getty III before me. I was tutored privately in preparation for an American high school, St. Stephen’s, an affiliate of the Kent School across town near the Colosseum, the Circus Maximus and the Roman Forum, what I like to call “Ruin Central.” With a student population of one hundred twenty-five, about evenly divided between boarding and day students, St. Stephen’s was surely the hippest school in the world, during what was the most permissive time in modern history, the Sexual Revolution, when it was “forbidden to forbid.”

I flourished at St. Stephen’s. The glib showman within me burst onto a social stage that for the most part was completely accepting of me. My first semester, I was labeled “obnoxious” by the older boys — an important-sounding, polysyllabic adjective that was popular at the time — and thrown in the fountain in the center of the school’s atrium nine times, more than any other kid. I kept a set of dry clothes in my locker and made it part of my clown shtick. The fountain dunkings stopped after I brought the house down by appearing as an insane Dolly Parton in the Christmas pantomime. Becoming the school clown has saved many extroverted kids from torment by older boys looking for a hormonal-rage outlet. All schools everywhere are anarchic corridas; in my experience, American schools are by far the most cruel and combative, even posh ones in Ruin Central.

That Christmas Eve, Dad drank until his sentimentality, psychosis and rage fused. He assaulted me as I was headed to bed, a twice-yearly occurrence that began when I was nine, and was so random that I could never anticipate it or avoid it. He pinned me under the Christmas tree and poured out his loathing inches from my face.

“Who do you think you are? The Prince of Wales?”

I was no longer “an American child.” I’d grown to be a spoiled European aristocrat who drank tea with his breakfast (“No American child drinks tea!”) and had no work ethic or “understanding of the value of money.” Even poor Italians consider money gauche, never to be discussed. It’s the same as mentioning one’s profession, if you insist on having one.

Dad couldn’t stand to have me around anymore—the mutual loathing was the fulcrum of nearly every discussion we had. His weekend reappearances from traveling Monday through Friday—he was the most flown person on Alitalia and TWA, simultaneously—were almost too stressful to bear. It was decided that I would go into boarding at St. Stephen’s, ostensibly to improve my grades under supervision during study hour. But it was a scapegoat’s banishment like any other.

If ninth grade was liberating and foundational for my future as a consummate outsider, my sophomore year was the happiest of my life. I returned two weeks late from a family road trip out West that could have been titled National Lampoon’s Texas Chainsaw Family Vacation, and was dunked in a communal pool of warming love, excitement and unfettered, largely unsupervised teen adventure.

The fresh faces in the students’ café, my personal cabaret, included Giulia Salvatori, a junior, daughter of French and Italian movie stars Annie Girardot and Renato Salvatori. Her fluvially smooth Parisian cool was captivating. At that point, I had no experience of Paris; Giulia set the tone and impression that it was a siren too hip and seductive to bother singing. She said little, smoked more sensuously than anyone, thanks to a generous, pouty mouth inherited from her mother, and dressed androgynously in a Last Tango in Paris, well-heeled, Euro-commie style — distressed denim, suede boots, big scarf, saddlebag across her chest en bandoulière.

Mind-blowingly, Giulia had her own semi-detached, one-bedroom apartment within a townhouse her father owned abutting the Teatro Marcello, walking distance from St. Stephen’s. I claimed it as my after-school hangout the minute I stepped into that teen heaven: a tiny bedroom, mostly taken over by a queen-sized bed; a small study with a minimalist desk and an overstuffed daybed; a dark-marbled, snort-coke-on-any-surface bathroom; and a living room with wall-to-wall carpeting, oversized bolster cushions lining the walls, and a stereo with the right records —no art, no regular furniture, ashram style.

If I look at the back room of the student café at school, I see no boys, just me and my seraglio of female friends that I cultivated not because I identified with girls, but because of my waning attraction for them, and my increasingly feverish obsession with guys. I was protected from my same-sex desires in the company of women.

Then I see a boy breaking into my seraglio, slipping in through the front door. Giulia pads into the bar with him trailing behind her. She’s wearing a scarf wrapped around her neck, which tells me the time of year is autumn. The boy is Oliver Stewart, a junior like her, so older than me, who normally hangs out in the school driveway with the moped clique — I’ve never even nodded to him to acknowledge his existence.

Oliver and Giulia are now a couple. Nobody asked my permission for this intrusion, to take over my prized princess, whose life I want for my own, movie-star parents and all.

It takes about ten minutes for me to realize Oliver is the most beautiful person I’ve ever seen; Giulia’s seal of approval enhances an attractiveness I’ve hitherto ignored. Half American, half Italian, he’s a little taller than me; a teasing, jocular-jock humor paired with teen Armie Hammer looks that will occasionally trap me in normal teen insecurities constantly on the highest alert, and will define my preferred type for the rest of my life.

Oliver stares at me, rarely looking away, like I am a favorite show that never grows dull. I’m always performing, dancing with my girls, raconteuring embellished truths, or outright extemporized fictions that elevate me socially and protect the fractured sense of self that every scapegoated child struggles to keep from overwhelming him. As Oliver’s persona invades and conquers my own, my mind crackles and superheats — I’m soon pinned down, conceding defeat enthusiastically, meeting his resolute gaze with a reciprocal smile.

COUP DE FOU

The three of us were over at Giulia’s almost every afternoon. While they had brisk after-school sex, I went downstairs to the kitchen and entertained Odabella, the cook. I learned to cook by watching and helping her. ‘James’ is a particularly hard name to pronounce for Italian and Spanish speakers. The first attempts come out “jay-ne”; when Italians read it out, it’s “yah-meh-seh.” They try to add the S, but it’s usually a fumble. Odabella threw her hands God-ward, gave up and dubbed me “Jean-see.” Oliver howled with laughter, Giulia chuckled, nibbled her lip. ‘Ginsi’ became my nickname. From Oliver’s mother, Luisa, we picked up his childhood nickname, ‘Papo.’

The moment my affection for him went from platonic to full-on Romeo limerence is a messily reconstructed memory. I see us on Giulia’s bed. She’s between me and him, spooning with him — lip nibble, lip nibble. “Coucou ai capelli,” she whispers to prompt him. Oliver does as asked, and twirls her curly hair, idly finding patterns with his fingertips. I’m jabbering, an extreme extrovert justifying his place in a throuple with two introverts, a version of Bertolucci’s The Dreamers: Ginsi, Giulia and Papo.

He kisses her shoulder, never taking his eyes off me. I crack a joke, probably at some less-popular kid’s expense, or mimic a teacher, and he guffaws — a generous, raspy laugh. My heart fuses with my stomach. Then: Snap! A new succubus emotion floods every cell of me: limerence, the obsessive form of romantic love, made more acute by my poor attachment styles.

Sex between men in Rome was everywhere, always covertly, in the musty shadows of ruins, public toilets, park bushes. It’s “a culture rooted in phallophilia,” as Oliver’s godfather, the gay writer and public intellectual Gore Vidal described it in a Vanity Fair essay about his appearance in Fellini’s Roma. The scene also features Oliver’s father, Donald Ogden Stewart, Jr., the editor of Playboy’s international editions and a former The New Yorker staff writer.

All Oliver ever mentioned about the mega-watt literary world he was born into was, “My grandfather won an Oscar once, for Best Screenplay.” At one time the highest-paid writer in Hollywood, grandpa Don, Sr. was also a member of the Algonquin Roundtable, wrote most of Katherine Hepburn’s lines, and browbeat FDR every morning with telegrams about how to run the country. As the Chairman of the Hollywood Anti-Fascist League and a bleeding-red commie, he was at the top of the McCarthy-era blacklist of banned Hollywood writers. At the time Oliver and I were falling into a deep bromance, Don Sr. still lived in self-imposed exile in London, as did my maternal grandfather and his second wife.

When Giulia wasn’t around, Oliver and I spent every moment together. As permissive and generous as her parents were, she was still under the strict curfews and expectations imposed on all Italian girls. Every other week or so, Oliver called me at school, when his mother was going out for the night, or was away, and invited me to spend the night. Donald and Luisa were divorced at the time. I waited for lights-out, slipped over the school wall, and hitchhiked to his place, exchanging Boy Scout sex for the ride—American kids of both sexes were preyed on constantly.

Papo and I hung around in our underpants, getting high. Depending on how severe the munchies were, he would cook either a half or a full kilo of spaghetti with his favorite sauce, “Latte, burro e parmigiano” — mac and cheese, now that I think about it. We slept together in his mother’s bed. At that point it was still strictly an erotic, no-homo pas de deux; brushing against each other, spooning for intervals, breaking away when we fell into deep sleep, then more accidental brushing and morning hard-ons when we woke up. He would give me a clean pair of his underpants to wear. Coincidentally, both Luisa and Mum bought us underpants from Marks & Spencer when they went to London to visit our respective grandparents. His were orange and red, mine white. He’d drive us to school the next morning on his motorbike.

One weekend when Giulia was away with her mother in Paris, Oliver took me to meet his father at his country house in Monte Argentario, near Porto Ercole on the southern Tuscan coast. Donald was puzzled when he met me. I was not his son’s usual motocross buddy; in other words, no teen papier-mâché mess of mud, indifferent clothing, scabs and bruises. He’d just returned from meetings in California with Hugh Hefner and had picked up new clothing that Oliver had requested to accompany this new, fashion-conscious throuple lifestyle with Giulia and James.

“It’s from a new store out of San Francisco called The Gap,” Donald said as we tore open the packages and found two complete outfits with canvas shoes, one pair beige, the other light olive. We took off what we had on, down to each other’s underpants. Donald protested weakly that he’d intended the clothes to be for Oliver, then didn’t say much else the rest of the weekend. I assumed he disapproved of me, like most American fathers, mine above all.

Luisa announced that her friend’s modeling agency was looking for boys; she wanted to take test shots of Oliver. He agreed, provided he could do them with me; Oliver relied on my showmanship to get through actions he found daunting, like dancing in a disco, or performing in the school play. As Judge Danforth in The Crucible, he looked straight into my eyes while he robotically said his lines, every rehearsal, each performance.

We donned our new Gap clothing, and I groomed both of us, slicking back our hair, gigolo-style. Luisa took the pictures on the roof of her building in the late afternoon sun.

While Giulia and Oliver went skiing in Cortina d’Ampezzo for winter break, I joined my family and the families of two of Dad’s close Cuban-American “business associates” in Davos, Switzerland. On Christmas Eve, he ambushed me in the narrow corridors of the chalet, slamming me against the wood paneling, so trashed he was staggering, but still far more powerful than me. He slurred and sputtered his litany of hatreds, capped by his usual intractable Yankee disgust for inherited privilege and elitism, “You think you’re the fucking Prince of Wales!”

Over the year between the previous Christmas and this one, I’d prepared a retort for that particular stock accusation: “If that’s not what you wanted, why send me to school with princes?” Blinking, he released me. I’d scored a rare victory, however Pyrrhic it would turn out to be.

I went to Paris with Giulia and Oliver for Easter break of ’79. Her digs in the Place des Vosges kicked her place in Rome from first to business class. She had her own duplex apartment in the attic of the Pavillon de la Reine, above Annie’s palatial space two floors below. I slept in the garret above the master bedroom, accessed by, yes, an iron-and-wood spiral staircase. We stomped around the most stunning city in the world with Annie, her entourage of handsome young actors, and her best friend, a beefy lesbian named Picolette, the verlans reversal of her real name, Colette Pico.

SAVING AMERICA FROM HUMANITY

The call from Mum came late in April. I took it in the lobby off the entrance to St. Stephen’s. “Dad is moving us back to New York,” she said. He wanted to save America from Carter and House speaker Tip O’Neill by working on the 1980 Republican campaign. Worst of all, his children were no longer Americans, and his eldest had become the fucking Prince of Wales.

Stung Ferdinand howled. Oliver freaked out with me. I asked to stay in boarding for my remaining two years in high school, but Dad wouldn’t pay for that. The point was to get me out of Rome, away from the palazzi, the villas, the louche aristocrats, the incipient communism.

Papo persuaded Luisa to let me live with them. But that idea collapsed after a couple of days, perhaps after Mum called Luisa. I got the bad news on the same phone in the entrance of the school. Oliver sounded coached: “Senti, Ginsi. I’m going to graduate next year. Then what are you going to do when I’m in college? You’ll be all alone here. You go first, get a giro going for us. Dai, New York’s the shit, man.” New York was the ultimate destination in those years — world culture bowed in the City’s direction, all day, every day.

That summer Oliver vacationed with Giulia at her father’s house in Porto Rotondo on Sardinia. I had a summer job as an interpreter and general assistant for a young Roman couple who’d been given a resort for Italo-Americans near our house Upstate as a wedding gift. I called Oliver whenever I could, barely covering a rising dread that he didn’t love me, he’d never loved me, he was trying to get rid of me. Then, some welcome news: he and Giulia were coming to the States in August with her mother and Donald to look at colleges. Oliver arranged for us to spend four days alone together in New York at the end of their tour, after Giulia had left.

Our last weekend together wasn’t what either of us wanted or expected. It rained, my first experience of New York’s sudden diluvial downpours, like an enraged firefighter wrenching open a hydrant, flooding the street, then turning it off just as abruptly. Oliver was friskier, more overtly sexual than ever. But my every molecule was dragged into a churn of unstable hormonal alchemy, blinding desire, limerent yearning, and that banshee scream of gay-sex taboo; for teens in particular, it’s a deafening death-metal concert bludgeoning you at hazardous decibels. I was distressed and morose, weighted by a terrible premonition that I would never see him again.

A few weeks after Oliver returned to Rome, I received a letter from him that he’d written on the plane, with stamps from the Vatican Post. It was full of his teasing, put into writing without the benefit of his laughter and a jocular prod in the ribs. My mindset chose to interpret it as insulting. I’d hoped for an affirmation of his love for me when I tore open the letter. Instead, his jokes became heckles, his encouragements scanned as insincere and patronizing.

A FORTY-YEAR EXILE

Over Easter break of 1980, while visiting my paternal grandparents in Florida, Mum and Dad called me into their hotel room. They sat side by side, facing me, Jack Nicholson and Natalie Wood as the American Gothic couple. I knew what was going to happen; I’d had a sense of this scene before, not a clear image of it—nothing quite so paranormal.

“We have some bad news,” Dad said. “Your friend Oliver is very, very sick.”

“Yes, very sick.” Mum echoed. Then she took the step that Dad couldn’t. “In fact, he’s dead. We’re so sorry, James.”

Oliver died while bathing. A carbon monoxide leak from the water heater in the bathroom of his family’s country house had caused him to pass out and asphyxiate. Tom Rockwell, a close childhood friend of mine in Oliver’s class, was with him and had discovered the body.

I had no reaction. I shed not a tear; I’d already pre-mourned him. I locked myself in the bathroom and sat in the shower for hours, until it stripped all the oil from my skin. I spent the night and much of the next morning trying to scratch off an invisible hair shirt that strafed my entire body.

Oliver died on March 24. I was informed on April 4, the day before the funeral — too late for me to get from Florida to Orbetello. Nobody in Rome had thought to call me. I found out about it almost by accident: A girl I barely knew from St. Stephen’s, who had also moved back to New York when I did, called our place on Gracie Square and left a message with our houseman, Dominic, who had observed my affection for Oliver, as he did everything concerning me. Knowing it was urgent news, he’d called my parents in Florida.

My heart and ego were pummeled that I’d been overlooked, but I was Italian enough to instinctively understand the brutta figura of who I was; being ignored was what I deserved. And despite Oliver’s constant efforts to assure me otherwise, I was convinced he didn’t care for me anymore by the time he left this world. Why should he care for me after death?

Once it was established that I would never make it back in time, my parents promised that I could go back for Oliver’s class graduation — Tom, Giulia and other friends in our small circle would be graduating, too. I would go to the grave in Orbetello. I would bury and mourn him then.

I stayed with Giulia when I got to Rome. But everything was different between us, forever changed. She had believed that she and Oliver were going to get back together again; I knew differently from my many calls with him, but didn’t say anything.

Gore Vidal gave the commencement speech, then Oliver’s friends went to Luisa’s apartment for a post-graduation party in his honor. My presence froze everyone with uncertainty about how to behave, what to say to me; they’d all seen Stung Ferdinand plenty of times. Luisa showed me Oliver’s room, gave me a print of one of the modeling test shots she took of us, my half of which I used for my senior yearbook picture at Trinity. Standing in his room, I mentioned the letter he wrote me.

Luisa’s face set hard, perhaps holding back tears. She turned away. “That’s the only letter he ever wrote anyone,” she said.

I returned to the living room. A twenty-three-year-old woman named Letizia introduced herself as Oliver’s occasional lover, not his girlfriend. Even if I’d also been having sex with adult men regularly, it impressed the hell out of me, and made me even more confused about who he really was in the end—he was grown up, while I’d remained a clingy lovesick kid.

I yammered away about my life in New York to make conversation. The awkwardness was stifling. I got up and followed Luisa as she left the room. Annie Girardot was observing the scene, her back to the wall of a corridor that led to the bedrooms. As Luisa passed her, Annie asked, in her heavily Frenchified Italian, what she could do to help. “Cosa posso fare?”

Not knowing I was behind her, Luisa replied, “Toglimelo da fra i piedi,” telling her to pull me out from between her feet. Annie saw that I’d heard, and quickly improvised with, “Perché non vieni a Parigi con me?” She brought me to Paris with her the next day.

A week or so later, Giulia showed up in Paris, angry with me, for no reason as far as I was concerned. Standing at her mother’s dining table, she spoke the fate-forming words: “Oliver non ti amava. Ti rispettava.” Oliver didn’t love me; he respected me.

With that, she kicked me past the friend zone, into the faculty lounge with teachers he would have remembered fondly from time to time, but wouldn’t have seen again. It was too much for my insecure, ashamed mind to step back from and read the situation differently, as I can now, post-Call Me By Your Name. Had I really been so insignificant to Oliver, neither Luisa nor Giulia would have reacted to my presence that way, which isn’t to say I didn’t seem delusional from their point of view — I did from mine, too.

A week later, I returned to New York. I hadn’t seen Oliver’s grave, hadn’t been able to mourn him — and I still hadn’t shed a tear. It didn’t cross my mind that I deserved anything more, a false conviction that would stay with me for four decades.

Sometime after I returned, I joined a group of Italian friends in their early twenties for a weekend at opera director Joseph Lee’s house in Southampton. I had a crush on Joseph, then the Rome correspondent for Interview magazine while he was apprenticing as an opera director. He was firmly in the middle of the Roman social scene. Joseph was also close to Gore Vidal, often invited for weekends at his Moorish cliffside villa on the Amalfi Coast, La Rondinaia.

I see us at the dinner table, Joseph’s friends Nancy to my right and Carlo to my left, Joseph opposite me at the head of the table. Midway through dinner, either Carlo or Nancy asks how Gore is. Joseph looks at me and says, “Gore’s devastated by the death of his godson, Luisa and Donald Stewart’s son.”

Less than a beat later, I open my mouth, letting Stung Ferdinand loose, bucking and snorting at a swarm of hurt. I bellow at the injustices of what happened to me, about who Oliver really was to me, although I always call him ‘best friend,’ never ‘boyfriend.’ The brutta figura combusting with gay shame stops me from allowing myself to think that way. Everyone is wide-eyed with shock, Joseph especially. We barely know what to say in reaction to an event like that now, much less back then.

Later, Joseph and Carlo make sure I’m okay in bed. Both look quite concerned, and that embarrasses me. I’m a shameful mess that cannot be fixed, despite my parents’ herculean efforts, a grieving, deluded, heartbroken faggot.

A STIFF UPPER LIP RELAXES

I began to have recurring, hyper-real dreams about Oliver over the next few decades. He was still alive and living in Argentina, or some other remote place; his death was the greatest of his pranks to get me out of his life, or a ruse because he was in danger. For those few minutes between deep sleep and being fully awake—dormiveglia, in Italian, literally “asleep-awakening”—I was convinced the dreams were the true reality of waking life, that I would lose him again somehow, around a corner, in a crowd, or when I looked away for a second.

I went back to Italy in 1984, four years after Oliver’s death. Mum and a trio of her fellow New York divorcée friends had rented a house together in Punta Ala, on the Tuscan coast. Now that we were years rather than months past her son’s death, Luisa seemed delighted to hear from me, and invited me down to Monte Argentario, an hour and a half by car south of where we were. She and Donald had remarried; their grief over Oliver’s death had brought them back together. They’d remodeled the house completely; most notably, they’d demolished the bathroom where Oliver died. The fact the house was all but unrecognizable from when I’d last been there helped stabilize my emotions.

Donald was his usual reserved self, an introvert just like his son. We discussed the biography he was writing about his father, who’d died shortly after Oliver, a sparse exchange much like any I had regularly with a male parent from my glacial, stoic caste.

Seeing Oliver’s younger sister, Daria, rattled me from skull to ankle bones: It was as if Oliver had transitioned to a young woman in the most spectacular, you-can’t-tell sex-reassignment surgery in history. The last time I’d seen her, she was a withdrawn twelve-year-old with curly, dark-brown hair. Now it was straight and dirty blond, like his.

“Oh! Wow!” was all I could manage.

“I know. Crazy, isn’t it?” Luisa said.

The next day, Luisa and I spent the afternoon alone together, snorkeling for female sea urchins and eating their roe raw with fresh lemon juice as we crouched on craggy shoals.

She took me to Orbetello Cemetery. It was crammed with tombs, staggered down a slope with a view of the sea. She described the scene of Oliver’s funeral, the traumatized St. Stephen’s kids, the keepsakes they’d put in his grave. I learned for the first time that yellow was his favorite color. How could I not know that? But having a favorite color is a young child’s preoccupation, not a teen sex god’s. He would never have set himself up for my teasing by sharing that detail, nor did he wear yellow.

Then I saw it: His name on a tomb. Oliver Ogden Stewart. I broke down like a New York summer downpour, no warning, zero to sixty tonnes of tears in under a second. It was real. He was dead. No prank.

Luisa grabbed my arm and pulled me away. “Smettila!” she said. “Stop it!”

She led me urgently from the otherwise empty cemetery. Her words summoned the inflexible decorum imprinted in my DNA, automatic reflexes inherited from the British that prohibit unseemly displays of emotion in public, even in the absence of other people.

By the time I got in the passenger seat, I was fully composed. Luisa had reclaimed her kinder, warmer self, as if aware that her own reflexes — after all, a young man crying in an Italian cemetery with no one around is hardly brutta figura — might not have been the most compassionate.

I left the next day to join Joseph Lee and his opera friends on Capri, restoring myself with a few energetic afternoons between the legs of a nineteen-year-old Roman named Fabio I met in the hotel swimming pool.

I haven’t returned to Italy since. Thirty-six years later, I still speak fluent, teen-level Italian with no foreign accent. But I haven’t been able to step back into that unfathomable sadness.

In the ensuing years, throughout many struggles internal and external, professional and personal, I subconsciously searched for a replacement for Oliver in different men: tall, blond, masculine, jocular-jocks, almost always bisexuals. It wasn’t a blinkered obsession; just as often, I settled for guys who were nothing like him. My attachment styles made it nearly impossible for me to maintain a healthy romantic relationship for long, in any case.

The waking-life-like dreams of Oliver persisted. He began to age with me. Then, after I began therapy in 2016, they ceased.

Daria Stewart died in 1999 of a heroin overdose. Oliver’s tomb was moved to be alongside his sister’s in the Protestant Cemetery in Rome, or so I surmise from a photo of their grave online. I didn’t know what more I could say to Luisa and Donald, or whether I should say anything at all.

Then I went to the screening of Call Me By Your Name at the Arclight Hollywood. Aciman, Guadagnino and Jim Ivory took a sledgehammer to the caliginous sepulcher of crystalized memories in which I’d entombed myself with Oliver. They preserved his name. Chalamet and Hammer looked like us. It was the same era. But this was a diametrically different perspective on our relationship than the one I’d held onto all those years: It presented our romance as real; a good, beautiful, even aspirational thing. There was nothing shameful or brutta about it; rather, we made a bellissima figura. It was still tragic, but not as turgidly funereal as my experience; there was even a lightness to the melancholy.

THE SOUL-SEARING VICE OF MANLINESS

Under the lemon tree in the garden with Wes, the most Oliver-like boyfriend I’d ever had, for whom I’d waited “a very long time,” I wrestled with my untethered grief, somewhat hoping he wouldn’t be repelled by my weird, un-American inability to move on all these years later —yet another shame heaped atop measureless others.

I woke up the next day bleary, headachy from the intense outpouring, remorseful that I’d overreacted. Wes had gone to work. Still shaken, I laid out the coincidences in an email:

“Dearest Howard:

You might remember me telling you on our drive to Malibu that I was raised in Italy. I was a teen around the same time as Call Me By Your Name takes place. I was very like Elio, even physically — a twink until I filled out in manhood. I was intense, intellectual, sexually precocious, a passionate “heart with legs”… . My speech, like all of my friends, moved in and out between Italian and English without thought. The French still ask me where I’m from in France. We lived in crumbling old villas, vacationed in them, went to school in them.

In high school I fell in love for the first time. Hit me like a train. He was a year older than me, a bit taller, half Italian, half American, athletic, a ladies’ man, a charming rake, even rode a motorbike — sexy as they come. We slept together as often as we could despite the girlfriends, wore each other’s clothes, even underpants. He was blond with aquiline features — Armie Hammer would be perfect casting for him.

His name was Oliver.

Howard, I cannot thank you enough for making Call Me By Your Name. It is personally the most important film I have ever seen. I am proud, grateful and honored to be associated with you. … Etc.”

Howard replied: “WOW James. Thank u. I’m speechless Xxxx H”

I didn’t think about the similarities much after that. I knew that if I spoke about the possibility that Call Me By Your Name was based on my life, people would think I was nuts. If I thought I was nuts, why not other people?

I cheered Howard and Jim Ivory on during the awards race. Wes and I watched the Oscars with an indifferent crowd at the State Social House cigar bar on Sunset. Even though the film didn’t win Best Picture, I raised a glass to Jim’s victory for Best Adapted Screenplay. I felt guilty about having wasted Jim’s time and dashing his hopes when the deal I’d worked on for almost three years fell through. For an instant, I allowed myself some satisfaction that he’d achieved this new piece of glory thanks to a story that might well have been based on my own love and suffering. When we left the bar, everyone who had met Wes was smitten with his warmth and charm, women and men alike.

We drifted apart a couple of years later. They say my teen niece wept steadily for twenty-four hours after I told her, as if her own romance had died. “I’ve never seen her like that,” her father told me. When her grief subsided, she declared, “You will get back together again. I’m sure of it.”

It hasn’t happened. She’s still sure of it.

Willfully shutting out Call Me By Your Name from my focus barely lasted longer than our relationship. A few months after Wes moved out, Hollywood’s exacting standard trade practices forced me to revisit the similarities between my story and the film, and to make choices that few screenwriters have ever had to contemplate.

Continued in Part Two.

Feature Image: Left: James Killough at 23, (Ph: P. Angers) Right: Timothée Chalamet (Ph: R. Afanador/TIME)

All images in this article have been composited and posted according to the terms laid out in Section 107 of the Copyright Act, and meet the criteria for “fair use.”

For more about James Killough’s relationship with Oliver Stewart, Giulia Salvatori and Annie Girardot, there’s a three-part essay on Pure Film Creative, Remembering Annie.