The Malcontents

Nobody has the right to appropriate untouchability, especially Americans.

RECAP OF PARTS ONE, TWO AND THREE

Over pillow talk with a longtime lover belonging to my Anglo-American Business varna (caste) and Highlander jati (subcaste), but as a Californian not from my Northeastern Establishment Protestant gotra (lineage), he mentions finding a YouTube clip of when I emceed the first televised Miss India Pageant in 1993.

I use the remembrance of that insane, glorious event as a portal to India’s misunderstood, complex social system, stating an irrefutable truth: “The Indian caste system is a highly successful, millennia-old eugenics program originally based on professional and temperamental aptitude that governs the lives of 1.2 billion people and uses ‘arranged marriage,’ or endogamy, as a euphemism for selective breeding.”

After deciding that my experience with untouchability needed its own space, I began to write about Jamuna, a Dalit (f.k.a. Harijan) who worked for me after I escaped the repercussions of the rigged Miss India Pageant and moved to Landour in the Himalayan foothills. Stepping into the subject opened up an entire tackle shop of worm cans, expanding part three into three parts of its own.

“Oh, East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet,

Till Earth and Sky stand presently at God's great Judgment Seat;

But there is neither East nor West, Border, nor Breed, nor Birth,

When two strong men stand face to face, though they come from the ends of the earth!”

— Rudyard Kipling, ‘The Ballad of East and West’

LORD OF THE PYRES

When I nudged Jumuna to get up from charan sparsh after he’d trekked up to Landour from Delhi to work as my houseman, and told him in rudimentary Hindi never to do it again — “You, me, both same are” — I wasn’t being a classic-movie American missionary feeling Christ-like, spreading the gospel of equality to the oppressed.

In the previous part of this essay, I deliberately left out the cringe-worthy last sentence, “Main bhi Harijan hoon” — “I’m also a Harijan.”

All non-Hindus are impure Untouchables/Harijans/Dalits. We’re all born “out of caste,” the origin of the word “outcast.”

I left it out because it belongs in this segment: That critical detail creates the basic overriding flaw in Isabel Wilkerson’s thesis — a euphemism for a theory, as in critical — in her book Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents (2020) and Ava DuVernay’s film adaptation, Origin (2024), which shoehorns a painfully small false equivalency between the Black American experience and the Dalits'.

They refer to it as a “thesis,” but nobody parses the difference; it’s disingenuous to pretend this wasn’t an attempt by the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America's Great Migration, named two weeks by the New York Times as the second-best book of the 21st century, to open up a new vein in the gold mine of critical race theory.

Being a foreigner and White in a land formerly governed by the British, where colorism is to this day an organizing principle, wiped away the same sort of treatment for me that Jamuna received from birth. Still, there are plenty of sacred places in India I’m not welcome because of my caste-less contagion: the Jagannath Temple in Puri and the Kashi Vishwanath Temple in Varanasi are two notable examples.

Maura Moynihan, daughter of the much loved late Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan of New York, was a teenager when her father was our ambassador to Delhi in the early 70s. A Black Irishwoman several notches above me in raconteuring, mimicry, and fluency in Hindi, I listened to her one night with respect and envy as she slayed a dinner table with a story about trying to get into the Jagannath Temple wearing just a sari, no choli top — stitched garments, introduced by Persian invaders to India, are often forbidden in the more ancient and sacred temples — insisting that she was a Pathani Brahmin from the Northwest Frontier/Afghanistan region, where skin tones tend to be fairer. The temple guardians still booted her White Untouchable ass out.

It wasn’t just admission to some of the more important temples in India that reminded me of my place. Now and then I spread my outcast’s contagion by coming into contact with sacred objects and symbols.

A month or so before the Miss India pageant and my escape to Landour with Jamuna, I found myself at the Imperial Hotel in Delhi on the men’s side of a wedding event for the crown prince of one of the major Rajasthani families. Le tout rajwara was there, the hall packed with his highnesses in full regalia: turbans crisply tied according to clan custom, embroidered silk angarkhas, ornate ceremonial swords held a certain way over the abdomen.

Pamela Rooks, director of a film I’d written that had just won the Film Festival of India, was openly in an extramarital affair with Jagat Singh of Jaipur, the younger half-brother of the maharaja — known to all as Bubbles because his father filled the pool at Rambagh Palace with champagne after he was born — and the only son of fabled Third Her Highness Gayatri Devi, the dowager princess.

A lovable, raging alcoholic who would soon die of cirrhosis — he reminded me of Dudley Moore’s character in Arthur as a modern Indian prince — Jagat handed me his sword to make it easier for him to slip away from the crowd for a few quick drinks at the hotel bar, unnoticed in plain sight by his long-suffering aide-de-camp and minder, Shakti.

I held the sword like everyone else, the hilt resting casually on the thenar webspace of my right hand (never impure left) between thumb and index finger, and continued a stilted, unwelcome conversation with an aggressively macho member of the cadet branch of the Jodhpur family I disliked immensely.

Too many minutes later, Jagat scooted back and grabbed the sword.

“I’ve just been told off. You’re not supposed to be holding this, apparently,” he said.

“Of course not: I’m an Untouchable, ya great eejit.”

“So easy to forget!”

I wouldn’t be surprised if after they returned to Jaipur, Shakti sent it off to a family pujari for a good purifying scrub in Ganga jal under billows of Vedic chanting.

It was in that moment, surveying the room of resplendent human peacocks, barely listening to the macho dullard, when my neurodivergent brain dissembled the world around me and reformed it as Shakespeare’s stage.

Why are Indian princes such a buncha frat jocks? Because… who better for the wily Brahmins and Baniyas to send off to war and bang a few heads than those who enjoyed doing it? So the caste system is Brave New World… no, more like brave ancient world because how long has this been… so long nobody knows, millennia, probably… that means arranged marriage is selective breeding by character trait and professional inclination, and… Genetic engineering. Wow!

From there I began to see the eugenics component of the caste system everywhere: the soft-spoken, ethereal Brahmin intellectuals and government administrators; the swaggering Kshatriyas like the one putting my ear to sleep; the energetic, opportunistic Wolf of Wall Street Baniyas; the servile Shudras in every household, tending the gardens; the impure Harijans born out of caste, sweeping, cleaning toilets and managing sewage, tanning hides, tilling fields, burning the dead.

Yes, the dead. Untouchability is all about the dead.

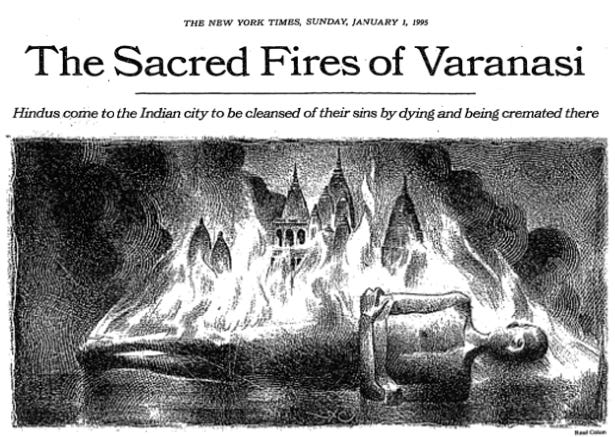

I recently revisited an essay I wrote for the New York Times Travel Section in 1995 about the burning ghats of Varanasi, when my friend Ben Ingham, an English photographer, and I had tea with the Dom Raja, hereditary Lord of the Pyres, an Untouchable prince of sorts, in his haveli overlooking the Ganga. He was young, our age, late twenties, short and rotund, his skin not so much a deep brown as charcoal black, making his vermillion lips stained from chewing paan look like a bleeding gash on a water buffalo.

He didn’t say anything and spoke no English. He stared at us unflinchingly as if he were Anubis weighing our hearts against Maat’s feather of truth. An interpreter from the local government brokered our request to get closer to the pyres of Manikarnika Ghat than was normally allowed for people who weren’t male relatives of the deceased, who must be Hindu.

Per ChatGPT:

Being cremated at Manikarnika Ghat and having one's ashes scattered in the Ganges River helps the soul attain moksha, liberation from the cycle of birth and death. Manikarnika is a bustling and deeply spiritual place, with cremations taking place around the clock. It is the oldest and most sacred ghat in Varanasi.

The Dom Raja nodded regally and stood. We followed him from the haveli down a cobblestone medieval lane to the burning pit under the soot-cover temple of Shiva in the form of Mahashamshan Nath, Lord of the Burning Ghats. A dozen or so pyres were in various stages of blazing to embers. Other doms bowed as their prince wove through the pyres as if walking through his private gardens.

The Dom Raja and his forefathers had been tending the most sacred burning ghats in India in the oldest living city in the world for centuries, longer than America had existed even pre-Revolution. The dead were his karma and dharma from birth till death, his place here and nowhere else, not in this lifetime, in this intense heat enveloped by the smoke and smell of burning sandalwood mixed with less-expensive mango, banyan and neem, here at a respectful distance among upper-caste mourners whose parents had come to Varanasi to die and hopefully break the cycle of karma.

Ben raised his camera to his eye once, lowered it, and said, “I can’t photograph this.”

NOBODY’S MACGUFFIN

Mahatma Gandhi blessed Untouchables with the name ‘Harijan,’ meaning “children of God,” during the Independence movement. Imitating other radical groups of the early 70s in the West, a militant social-justice group, the Dalit Panthers, steadily imposed the word ‘Dalit’ — meaning “downtrodden” or “oppressed” — a term that didn’t come into common usage until the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder in June 2020.

While I see the point in rebranding with a word that draws attention to their plight, ‘Dalit’ misses the more esoteric meaning that ‘Harijan’ implies in Eastern spiritual practices, that as they are closer to God than anyone, a variant on Christ’s “Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth.”

Thinking about it in those terms, I understand that Jamuna is the most enlightened being in all the stories I have to tell: he was nearly egoless, a paragon of self-abnegation, his identity as the Lambu Shehzade ka Chela bound to mine — “Who you are, he is.” Every rupee he earned was sent to his family, another reason he never took a day off or spent money on himself. He was the aspirational javan-mard of Sufism, selfless, brave, humble, chivalrous, offering loving-kindness to all.

With that sentiment, I’m coming perilously close to the ending of Rudyard Kipling’s Gunga Din, “You’re a better man than I am, Gunga Din!” The poem is a backhanded ode to a regimental low-caste bhishti water-bearer narrated by a working-class soldier in Cockney dialect, creating a class equivalency between the two characters. Most uncannily, Jamuna and Gunga/Ganga are two of the seven sacred rivers of India, and normally girls’ names.

With perhaps the luckiest timing in publishing history, Wilkerson’s Caste was released in August 2020, when “peaceful protests” still raged in Liberal bastions on both coasts, incited by BLM’s evidence-defying claim that Black lives didn’t matter. I will never read it; its thesis is beyond “flawed,” as a German scholar politely calls it in the trailer for DuVernay’s film adaptation.

Jordan is a young Black friend who works at my local Trader Joe’s. As if summoned by my thoughts when I was at the cash register a few weeks ago, looking dazed from having spent three weeks trying to write the third part of this series that’s now been broken into three parts of its own, he asked me if I was okay.

I’m not one to hold back thoughts about American antiracism with Blacks. Since the troubles in June 2020, I’ve taken every opportunity that I’ve had to speak to Black people I’ve met casually, usually Uber drivers, to express my point of view about how damaging critical social justice has been to the mindset of the very people it’s meant to help.

It has invariably been appreciated. I’m not the usual White person repeating, “I can’t speak for the Black experience” like a moronic, cowardly version of Robot from Lost in Space stuck on repeat, thereby certifying what isn’t an experience so much as it’s the Black perception of the White experience of Blacks.

Generally speaking, it’s way off the mark.

I’ve known discrimination my whole life, a lot of it, so much I have no real measure of it. Much of it was from my own family. I doubt there’s any straight Black American who can come close. I know the feeling that you’re an outcast in an upper-caste world so well it’s a reflex.

I told Jordan about Wilkerson’s book and DuVernay’s film adaptation, how bogus and damaging the equivalency they make with Dalits is, and why. Like a Black Uber driver a few nights earlier who took my email address at the end of the trip to give to his son if he had any questions, Jordan dashed to the manager’s station to grab a pen and paper.

It was then that I noticed the cashier, a White trans woman, her mouth agape — seriously — at the insanely taboo conversation she was listening to, stunned that Jordan was not only fine with it but was writing down the name of the movie so he could discuss it with me further.

A few days later, he came up to me again while I was pretending to ponder cheeses, but in reality working out a complex thought.

“I liked it. Very emotional,” he said. “But I can see why you would have a problem with her thesis about the… um…”

“Untouchables. Harijans. Dalits.”

“Yeah, that scene when they were cleaning the toilets was tough to watch.”

You don’t know the half of it, son, the never-to-be-unseen pummeling my mind even now…

He reasoned the way everyone who sees the movie but hasn’t read the book does: “It’s more about her journey, you know —”

“To self-realization.”

“Yeah.”

“DuVernay had to insert a character arc. It’s a mandatory part of the narrative in American filmmaking.” Just as she has to “shed light on the human condition.” But that light isn’t true insight into humanhood, merely a limited choice from a set of corny, studio/network-approved American ideals, virtuous lies endlessly repeated.

“Yeah. The thesis itself is more her motivation for her journey —”

“That’s called the MacGuffin, the journey’s catalyst, but not its point.”

“Right.”

“It’s still outrageous.”

“Yeah. I get that.”

It’s also about the book, not the film adaptation; if they had adapted it more literally, it would be a docuseries with no fictionalization devices like MacGuffins that diminish the experience of others for the sake of shoehorning a self-aggrandizing thesis, or character arcs and pulling emotional strings.

That had already been done with Hulu’s 2023 revisionist history docuseries The 1619 Project, based on The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story an anthology compiled by Nikole Hannah-Jones and The New York Times Magazine, and executive produced by Oprah Winfrey. That was also problematic, but not to the degree of Caste, in my opinion.

Here’s what Hannah-Jones and Wilkerson’s books are: the fictitious novel We’s Lives In Da Ghetto in the movie American Fiction, written by Issa Rae’s wonderfully nuanced, deadpan character Sintara Golden. I almost coughed up a lung laughing at the book-reading scene.

They’re part of a literary and cinematic New Blaxploitation that isn’t nearly as fun as the original and ten times more damaging to the people it purports to help by “illuminating” their struggle, to borrow one of upper-class Haitian American Claudine Gay’s more inappropriately lyrical words when she was still President of Harvard University.

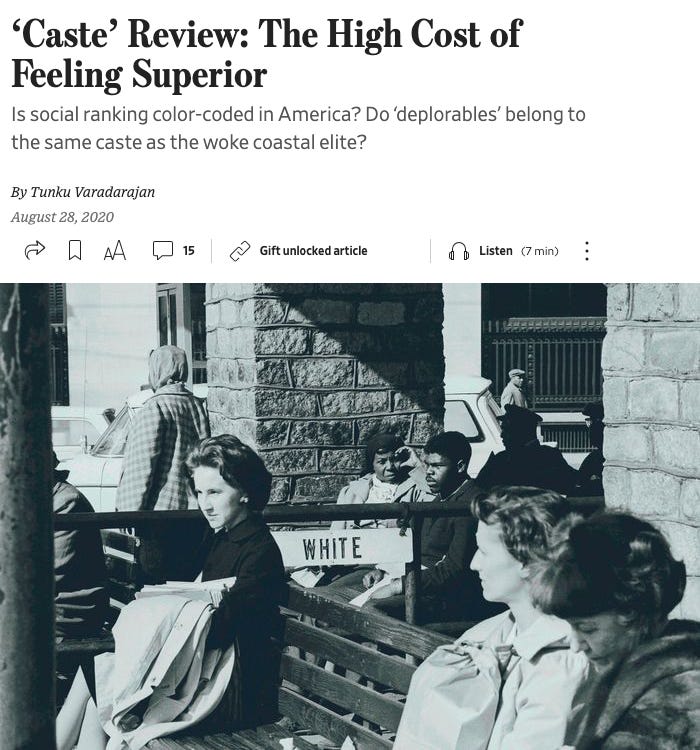

There was only one negative review of Wilkerson’s book, written by the only Indian critic of a major outlet to review it, Tunku Varadarajan for the Wall Street Journal. Unless I’m missing reviews from other South Asians, it should be considered the only informed and legitimate review.

Varadarajan has to tread carefully into untouchability — like Kamala Harris’ mother, he’s a Tamil Brahmin. If read through the lens of oblique British phrasing, it’s more scathing than it seems:

Ms. Wilkerson sows confusion in the reader’s mind, however, by declaring that “caste and race are neither synonymous nor mutually exclusive” and by using the words almost interchangeably throughout her book. “In the American caste system,” she writes, “the signal of rank is what we call race, the division of humans on the basis of their appearance.” Race, she continues, “is the primary tool and the visible decoy, the front man, for caste.”

And what, exactly, is caste? To Ms. Wilkerson, it is “a fixed and embedded ranking of human value that sets the presumed supremacy of one group against the presumed inferiority of other groups on the basis of ancestry.”

You would be right to ask how a caste system—so defined—is really that different from a race-based one in the American context.

Ms. Wilkerson sets up her system of caste by shuffling words around... She tells us that she uses the term dominant caste “instead of, or in addition to,” white and subordinate caste instead of African-American. Yet she never offers a convincing argument for why American history and society are better examined through the lens of caste than of race.

Bear in mind that the reviewer is an India-born member of the real caste system who is fully aware of what it is, but is too intrinsically ashamed to explain it.

The only binary comparison based on race that Wilkerson could make with India is the fairer-skinned White “Aryans” of the North and the darker Dravidians of the South. But even that’s too tenuous to be worth anything more than cursory consideration in a conversation with yourself in front of the cheese section, not in a book, certainly not a movie adaptation.

The Martin Luther King story about his visit to a school for Untouchable children in 1959, in which the headmaster introduced Dr. King as “a fellow untouchable from the United States of America,” is another excellent example of the abuse of American privilege by the modern antiracism movement. I’d never heard it before, but it’s almost certainly apocryphal.

Keep in mind all of the protocols and etiquette that I’ve described so far — they don’t scratch the surface of Indianness. The notion that a headmaster in Kerala in 1959 — 35 years before my experience with Jamuna — would effectively put himself and the children in his care on the same level as a revered civil rights leader, known to all as the American equivalent of Mahatma Gandhi, savior of the Harijans, and a guest in India to boot, is unthinkable, likely impossible.

It assumes a view of the individual and the supremacy of his ego that the headmaster would’ve had to live for several years in America to comprehend. When he did grasp the unseemly solipsism of it all, he would only have been more shocked and appalled, all the more reason not to say it.

The more likely scenario is Dr. King expressed something similar to what I said to Jamuna after I stopped him from touching my feet in charan sparsh when he first arrived in Landour, “I’m also a Harijan.” As a fellow American with the same mindset, he probably said to the children, “I’m your fellow Untouchable from the United States of America.”

If it was said at all — the story was debunked in The New Yorker — it was likely Dr. King’s own words twisted into the headmaster’s so the Untouchable could bestow the halo of his oppression more truthfully, rather than Dr. King taking it for himself.

VIRTUOUS LIES

Wilkerson, DuVernay & Assocs. had no problem taking the halos of 200 million Dalits for themselves. Their flagrant, self-absorbed brand of American privilege, which callously ignores the sentiments of Dalits in ways that wouldn’t be tolerated for five seconds if roles were reversed, would be laughably ironic if this Selfie Era out-of-control bonfire of our vanities didn’t make me squint and back away.

When Oprah labeled Caste “the most important book I’ve ever chosen for my book club,” she institutionalized a new lensing of a false oppressor-oppressed dynamic that is not supported by data-based evidence; on the contrary, the evidence dismisses all modern antiracism claims — other than MAGAs, nobody I know of who has supported the social-justice claims over the past eleven years since critical theory broke out of academia and into the mainstream has bothered to check it.

If we take one of BLM’s more successful canards as an example — Blacks are being slaughtered randomly by police; therefore, their lives don’t matter — the data states that Americans of all races have a 0.0035% chance of being shot dead by police, a little less than being killed by fireworks. There’s no statistically significant difference for Blacks.

That meets the criteria for “vanishingly rare.”

I’ve yet to speak to a Black person who doesn’t believe it’s a real threat. Sure, there are instances like Breonna Taylor and more recently Sonya Massey, but they are isolated, freak incidents. Still, they are held as evidence that simply being Black might get you killed.

A few years ago, a young White prom-king type who lived two buildings away from me in West Hollywood intervened when he heard his neighbor being assaulted by her boyfriend. When the police barged into the apartment, they shot the prom king dead. This is the West Hollywood Sherriff’s Department, the same team that keeps a Pride Parade of five hundred thousand people safe every year.

It can happen to anyone. The police also tend to be authoritarian dicks to everyone.

The difference is perception. When I got hauled over a few years ago by a White cop in Hollywood for jaywalking across an empty street and he screamed at me about “the people I’ve had to scrape off the road from hit and runs,” I had the option of either clapping back with my true White privilege — “Sorry, officer, but I’m a native New Yorker raised in Rome…” — or doing what I did, which was listen respectfully, knowing that this was likely PTSD from some horror he witnessed in Iraq that he had to scrape off the road. There was also the possibility of an impoverished, abuse-ravaged childhood, perhaps in the legendary L.A. foster care system.

I would’ve certainly seen the situation differently had I been Black with little experience of Whites — a crucial difference, in my experience — whose perception was entirely formed by characterizations of us as having “racism in [our] DNA LOL!” as a guy wrote to me on Grindr during the BLM troubles of 2020 after I rebuffed his request to engage in raceplay, in which I would pretend to be the abusive plantation master and he the slave.

I’d replied, “First of all, I’m a Yankee…” inadvertently shaming his fetish with my righteous indignation. Being a Yankee means nothing out West; there’s no collective memory of the Civil War like there is in my natal world; Dad’s living room was a shrine to our fallen, maimed, and those who made it through intact in body but with shrapneled minds. And you want me to roleplay a Southern slaveowner?

He let loose a racist tirade I’ve never heard from a White person as if it were his birthright — from where he and most Black Americans stood, it was.

As a menacing-looking “natural dom top,” I get requests like that a couple of times a year. After June of 2020, it was a few times a month for the rest of the year.

I managed to engage with less shaming and more compassion with another request for raceplay a week or so later; I remember that the protests were still immobilizing my neighborhood, the gay center of L.A. He admitted that it was nearly impossible to find White men willing to oblige, even in the South, where he was from. He also said, “What’s going on now [with BLM] is going to set race relations back decades.”

“Nah, it won’t,” I wrote dismissively. I’ve rarely been so wrong.

Like studio/network-approved American ideals about the human condition, these perspective-based opinions intended to reinforce historical narratives that are largely no longer true are what critics of the social justice movements excesses have dubbed “virtuous lies,” repeated endlessly in an echo chamber until they become “real truths.”

When Wilkerson insists that “caste and race are neither synonymous nor mutually exclusive” she’s engaging in the sort of critical-theory doublespeak that makes nonsense sound reasonable and highminded. Most people who read her book already share her perspective, reinforcing groupthink. With every added intersectional link — in the case of Caste between the current American social order, the Indian caste system and untouchability, and Nazi Germany — it becomes all the harder to escape from.

It makes no sense to my sort of neurodivergent brain why Whites would want to uphold this toxic groupthink with “I can’t speak for the Black experience.” But it’s also hypersensitive and empathetic. Having been gaslighted by my own family for most of my life, surrounding myself with people who reinforced that terrible whipping-boy “comfort zone,” how the vast majority of Black Americans construct their shared reality about Whites and being born into an oppressed class from which there is no exit triggers a reaction that explains the word ‘heartbreak’: it’s as if it splinters in my chest, flooding my throat at the base of my neck with sorrow and indignation over the unfairness — it’s a malignant and unnecessary connivance that is too vast and ingrained for me to undo.

The dangers of the social justice movement’s specious intersectional comparisons, both historical and contemporary, between America and completely different socio-cultural groups and nations leaped to the forefront after Hamas’ October 7 terrorist attacks.

Words like ‘apartheid’ and ‘genocide’ were warped and deliberately applied to a nation founded by a people for whom the word ‘ghetto’ was coined in Venice in the early 16th century, when they were confined in an area of the city under the sort of restrictions that defined apartheid-era South Africa.

For thirty years or so of my life, I wasn’t allowed to be in the Harlem and Spanish Harlem areas, or three square miles. of the island I was born on unless I was accompanied by Black women, not men — in a city where every block outside of the posh neighborhoods was a gang’s “turf” Black men might have made it worse. This was entirely by virtue of the color of my skin.

I would never call it “apartheid.”

I was at Barney’s Beanery in West Hollywood with my boyfriend one boozy night in 2018. It wasn’t a place many gay couples go; until 1985, there was a sign over the bar saying, “Fagots [sic] Stay Out.” But we prefered straight bars to the 18 or so establishments in “the Times Square of Gay,” as I call it, down the road.

I was on the porch talking with a middle-aged Black guy in the entourage of a long-has-been hip-hop star of the 90s. By the looks of it, they were mostly in some sector of L.A.’s sprawling entertainment industry, likely music.

“I’m from New York,” he said.

“Me too.”

“Oh, yeah? There’s a guy from every borough with us tonight.”

“Which are you from?”

“Brooklyn. You?”

“Manhattan.”

“Oh, yeah? Which part?”

“Upper East Side.”

He whooped, dashed to the entrance of the bar, and yelled to his friends, “Hey! There’s a guy from the Upper East Side out here.”

Within a few seconds, I was surrounded by five posturing Black entertainment execs glowering at me, stoned and drunk. Harlem was the largest, of course, his suit the nattiest.

I burst into a White version of Dave Chappelle’s “stoop chuckle,” as I call it, a mix of genuine laughter and jocular contempt reminiscent of Muttley the cartoon dog’s snicker.

“Are you fucking kidding me?” I said. “Look at you! You guys are still doing this shit, huh? ”

They snapped out of it, and we partied like New Yorkers used to back in the day when the streets of New York were ruled by Blackness, every inch of every subway car tagged with graffiti, Downtown galleries bristling with street art, shoulder-held “ghetto blasters” jamming backbeats into the undrownable din of the City.

Epic hangover.

BIRDS OF PREY

Most people don’t know how a web browser works. Like all things computer, it’s constructed in our own image, so to speak, to mimic how the brain functions. It’s an interface that grabs a staggering amount of information pulled from the internet and reassembles it in a coherent format that we’re accustomed to; for the most part, the result scans like a newspaper from Harry Potter, with moving rather than static images.

If you control/right-click on this page and scroll down to Inspect, you’ll see the raw information the page is receiving. Every line of code is pulling in even more ones and zeros in the form of bytes. The average homepage of the New York Times contains 40 million combinations of ones and zeros.

People assemble their interpretation of the world, or subjective reality, roughly the same way as browsers, with neurons representing a more complex form of bytes and synapses as conduits between them like the interconnects in AI chips running neural network accelerators, much like thoughts racing around a treasure hunt of information, collecting and comparing so fast they’re no longer even a blur, they’re invisible to human perception.

We all know what happens when there are bugs in the coding. AI hallucinations have decreased significantly since ChatGPT was rolled out, when its sensitivity guardrails made reasonable discourse and queries about society and culture so annoying I stopped using it for months.

I believe the virtuous lies of the social justice movement embedded in the guardrails were reduced after Sam Altman rebounded from a failed coup by members of the board, who were part of the do-gooder, egotistically named Effective Altruism movement. Those discrepancies might’ve been the cause of the hallucinations: AI was forced to analyze information within subjective social-justice parameters that clashed with objective raw data. Just as the virtuous lies of critical theory caused what Elon Musk called “the woke mind virus” in humans, coding cognitive dissonance into versions prior to the current ChatGPT 4.o caused it to have HAL 9000-type psychotic breaks.

ChatGPT calls my thesis “an interesting perspective… it's possible that overly restrictive measures could interfere with the model's ability to analyze and present data accurately.”

The point is that our brains react no differently when fed disinformation. Liberals can scoff at MAGAs and their conspiracy theories, but which is more dangerous, the conspiracy theory about Hillary Clinton’s campaign was running a child sex trafficking ring in a pizza parlor in New York, or the lie that Black lives don’t matter and that George Floyd’s murder was a hate crime, which forced much of Congress to literally bend the knee to its realness, Mitt Romney included?

Here’s why I focus on the egregiousness of the book more than the film, made under constraints that don’t exist in publishing: The title is Caste, not Origin. That is the rubric that frames Wikerson’s entire thesis.

The subtitle, The Origins of Our Discontents, is Wilkerson’s prestige-borrowing play on the opening line of Richard III, “Now is the winter of our discontent.” “Discontent” downplays the staggering amount of unjustified rancor that pervades these buggy narratives and catchphrases like, “Race is America’s organizing principle.” It’s only that to an overly influential and loud portion of the 13% of the population that identifies as Black, who also use colorism, a concept most non-Hispanic Whites are unfamiliar with, as a form of social ranking.

Let me split nuances in true critical theory fashion. “Discontent” is a feeling of dissatisfaction or unhappiness with a situation or condition, like you’ve gorged too much at Thanksgiving and need to lie down on the Antebellum chaise lounge to ease the pressure on your digestive system with a polite belch and a silent fart.

In my lexicon, Wilkerson, DuVernay & Assocs. aren’t merely discontent, they’re professional malcontents.

Per ChatGPT, malcontents “are people who are dissatisfied and rebellious, often expressing their discontent through active opposition or complaint.”

With critical race theorists having exhausted all possible domestic intersectionalities to justify their malcontent — and no doubt under great stress to follow up her Pulitzer-winning book, the second-best of the century, with something audacious and groundbreaking — Wilkerson actively stretched her discontent all the way to the opposite side of the world to cherry pick the Indian caste system.

I’ve been trying to introduce Americans to India for 35. Indian feelings matter, but not to Wilkerson, DuVernay & Assocs.; American privilege and identity supersede the rest of the world’s — it’s “my truth over objective truth” or nothing.

Throughout this dreary critical theory-sodden era, Grandma Mary’s favorite joke pops up right on cue: E pluribus unum means “every man for himself.”

I’ve long said to people, “If you want to know what pagan Europe was like, go to India and observe Hinduism.” Monotheism has created a duality between man and the divine that pantheistic cultures didn’t perceive. The gods were everywhere, in everything, inseparable from the human experience.

The caste system isn’t systemic in the sense of the rule of law, or social hierarchies, whether codified or informal. It is an inseparable part of Hinduism, of dharma, of a person’s place and relationship with Existence. There is no duality: the divine isn’t in everything, omnipresent and omniscient like the Judeo-Christian godhead, it is everything.

As the only White emcee of the first televised Miss India Pageant, I won’t allow cherry-picking the caste system by a privileged American malcontent wielding a Pulitzer like Thor’s hammer, whose sole purpose is to create a specious false equivalency to bolster racist tropes about Whites and the American social system.

Wilkerson doesn’t get to take something so monumental and complex from a culture she cannot possibly understand properly that is Western reality turned upside down through a rabbit hole in the looking-glass and use it in Oprah’s most important book, ever, followed by a Hollywood film adaptation, sealing it with Dr. King’s halo for good measure.

If you break out something so significant and expensive in terms of human lives and their experience, you own it. All of it.

With that approach as well my hypersensitive neurodivergent compassion for the reasons she and so many others in the Black community cling to explanations of why they are being held back that are by and large no longer valid, let me offer a few more counterpoints to Wilkerson’s thesis:

Blacks aren’t black White people. Dalits are as Indian as all the other castes, perhaps more so if my Adivasi original-dweller observation is valid — I’ve included the transcript of a dialogue with ChatGPT about that at the end.

Blacks are another race and ethnicity altogether, a culture that in my view is matriarchal, likely a holdover from the slave-owning, matriarchal Ashanti Empire in what is now modern Ghana.

Now that’s a Black American origin story I would read and watch, narrated by Tyler Perry as Madea, intercut with hard-hitting interviews by Coleman Hughes with Mmes. Wilkerson, DuVernay & Assocs., Oprah, the Three Furies of BLM, Whoopi, and other heavy hitters of the Black Matriarchy — it’s very much a thing, far more real and problematic in terms of negative influence on young Black men than a comparison between Black Americans and untouchability.Why just Dalits? They’re by no means the only oppressed group in India. Per the Government of India’s affirmative action program, called ‘Reservation,’ the oppressed include Scheduled Tribes (ST), ~105 million people, and the Other Backward Classes (OBC), another 35% of the population, made up of the lower Shudra Laborer Caste and other non-Hindu groups that are casteless.

That was rhetorical. We know why just Dalits: STs and OBCs don’t have the drama of Untouchable stigma, impurity, and outsiderness that makes Wilkerson’s binary “urgent and important.”Blacks aren’t considered impure by religious proscription. Segregation legislated by Jim Crow laws in the 14 former slave states, or <30% of the population up until 1964, was true American apartheid. Water fountains were separated for fear of contamination. Racial intermarriage, or miscegenation, was illegal in many places until 1967.

As a gay man of a certain age who survived the AIDS Crisis, I understand what being considered impure and contagious means. I wasn’t allowed to give blood for most of my adult life, from 1983 until 2020, when I had to wait 3 months after having sex. That quarantine period was removed in 2023, making it a total of 40 years of true systemic discrimination.

I can’t even remember the number of discriminations I’ve been subjected to for irrational fear of contagion. In 2010, I was sharing a house in the West Village for a couple of weeks with two middle-aged women I’d known for a long time, an Indios Latina and a Middle-Easterner. After I cut myself badly in the kitchen one day, they freaked out and demanded to see an HIV test. They began removing the modem from the house during the day so I wouldn’t download whatever it was that gay men infected the internet with.

No matter what I said to Jamuna in a moment of unseemly grandiose altruism when he joined me in Landour, I’m still not a Dalit.

The big question is why India — a culture we associate with spirituality, yoga, and enlightenment; with Mahatma Gandhi’s satyagraha, pacifism and nonviolent resistance, the birthplace of Buddha; with charmingly singsong accents, gently swaying heads, never saying “no”; a country that never tried to conquer her neighbors — would also have the worst of oppressions as an inextricable part of her main religion, a fifth caste as a non-caste, a thoroughly Brahmin concept.

Untouchability is all about the dead. That was my realization while being scorched by the pyres of the burning ghat with the Dom Raja of Varanasi. The stigma of impurity likely comes from the handling of corpses still contagious with the diseases that killed them.

In the “Land of Sudden Death,” as the British called it, plagues and epidemics are on another level of severity, so frequent they barely make the news. It has to do with the climate, the pools of stagnant water created by yearly monsoons that become fetid during the scorching summer months. Whatever was growing in those giant Petri dishes is then washed into the water supply during the subsequent rains.

Before modern medicine, it must’ve been the outbreaks similar to the Black Plague in rapid cycles. Perhaps it became a matter of necessity to institutionalize keeping Dalits from coming near people as a way of quarantining them. We know that Judaism and Islam forbid pork because of fears of disease, enshrining it in strict religious scripture and practice.

Several academically sound studies have been done over the past century that agree with my assumption. May ChatGPT guide you.Jamuna’s people don’t enjoy nearly the prestige and worldwide cultural influence that Black Americans have, certainly not in India. There’s no Dalit singer worth the equivalent of Rihanna’s $1.4 billion; no Dalit hip-hop stars designing for Parisian luxury brands; no f.k.a. Untouchable cricket players signing the likes of Patrick Mahomes’ $450,000,000 contract. How is it possible to ignore the staggering contributions of Black Americans to the current global zeitgeist in favor of this insistence on being seen as “the subordinate caste,” known in critical theory as “the subaltern,” a term coined by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, a Bengali Brahmin, who arguably speaks more willfully obfuscatory jibberish than Judith Butler herself.

Data don’t support anything near a comparison between discrimination toward Blacks and Dalits.

According to the FBI, there were 6,557 race-based hate crimes in 2022 meaning it affected 0.002% of the overall U.S. population of 341,809,591.

Of those, 3,424 hate crimes against Blacks were reported in 2022, meaning 0.0067% of the ~48 million Americans who identify as Black. While that represents 50% of all race-based hate crimes, there is one striking anomaly between Blacks and all other races: the category of the crime.

Generally, most hate crimes fall into four major categories:Intimidation.

Destruction/Damage/Vandalism of Property.

Simple Assault.

Aggravated Assault.

I can’t count the times I’ve been subjected to homophobic intimidation and simple assault, beginning with my father. Some notable occurrences were by Black men, not just the anecdote about the night at Barney’s Beanery, where the ban on faggots was lifted only forty years ago, twenty years after the Civil Rights Act, by which LGBT people are only partially and tenuously covered.

It’s with that authority that I discount the Intimidation and Vandalism categories as being true hate crimes against individuals, including against gay men and Whites.

Intimidation and Vandalism account for 37% and 23% of hate crimes against Blacks respectively, or a combined 60% of incidents. They account for 30% and 15% (combined 45%) of hate crimes against gay men, 25% and 10% (combined 35%) against Whites.

The total amount of what I consider to be true hate crimes — simple and aggravated assaults combined — against Blacks to 33% of total hate crimes reported, or 1,130. In other words, it’s not an existential threat in the least — it’s vanishingly rare, just like police shootings.

I ran the numbers through ChatGPT, which is excellent at analysis: “A Pew Research Center survey found that Black Americans are more likely to perceive unfair treatment by police and are significantly more likely to report experiences of being unfairly stopped due to their race.”

I’ve used the word 'perception' deliberately throughout this piece for that reason.

Blacks commit 21% of hate crimes against all groups, including the LGBT community. According to FBI data from 2022, Black men, or 6.5% of the population, commit most of those crimes, meaning overrepresentation by a factor of 3.25.

Forget about a Dalit committing a hate crime against an upper-caste Hindu in most of India; if he fought back against violence with violence, his entire family could be wiped out.Officially, 0.065% of Dalits are victims of caste-based hate crimes a year, or 8 times more than Blacks, if we keep Intimidation and Vandalism in the overall total. That’s being generous: Dalits are perpetually intimidated, from birth till death. You also need personal property to have it vandalized, which a negligible percentage have.

Crimes against Dalits are severe, on the aggravated assault and murder level; it would likely need to involve a death for them to report a crime committed by upper-casters. Harassments we would consider punishable crimes, like being beaten, are taken as part of being who they are in society.

130,000 is a suspiciously round number compared to the FBI’s granular stats. Those numbers are reported by the Government of India, which is highly sensitive to international perception. Of all the many things Indians are shamed for, untouchability is likely the worst.

If we take GoI’s official numbers of 524,000 Covid deaths versus the WHO’s estimate of 4.7 million — I still think that’s low — we might hypothesize that the true number of hate crimes against Dalits should be increased by a factor of nine to 1,170,000, or 0.585% of the Dalit population of 200,000,000.

That works out to 86 times the hate crimes against Blacks, more if you limit the hate crimes to just assault and homicide. I can’t find data anywhere that shows any Blacks have been killed over race issues in the modern era. And it is specifically Blacks in present times that Wilkerson is referring to, with the usual opportunistic temporal distortion of presentism.

I don’t know if Wilkerson drew a comparison between African slaves and Indian slaves today, many of whom are Dalits. I can only hope she didn’t go that far:

According to ChatGPT, there are ~14 million slaves right now in India. There were ~10 million enslaved Africans throughout the entire history of slavery in America. Slaves in India are often given as children by tenant farmers to settle debts to landowners, or because they can’t afford another mouth to feed — better a life as a slave than no life at all.

It’s a fate that could easily have befallen Jamuna. Slavery is as much an issue for his people today as it was for the African ancestors of modern Black Americans seven generations ago.

Jamuna doesn’t need to claim pseudoscientific constructs like “generational trauma” as a way of keeping White people on the back foot and a zombie oppressor-oppressed narrative on life support. Millions of his people are living as valueless slaves in the here and now, while you read this.African slaves were expensive, not expendable like most Dalit slaves. They were insured commodities that needed to be kept healthy and compliant to work effectively as indispensable parts of a large-scale pre-Industrial Revolution agriculture model.

The conditions under which Dalit slaves live and toil are unimaginable to most Americans, born as they are into a perpetual gulag concentration camp of heat, dust, and conditions so unsanitary they defy my ability to describe them, their flimsy shelters shredded annually by torrential rains or property developers. There is no escape from it to freedom in the North, no majority-Dalit island nations in the Caribbean, no Dalit equivalent of the entire continent of Africa to dream and be proud of.

How does any of the above relate to the modern Black American experience?

In a therapy session a month ago, I tried to explain the egregiousness of Wilkerson’s thesis. When I got to the slavery part, indignation clamped my teeth shut. My ice-blue White gaze jolted from my therapist to the ceiling, where I was blitzed with rapid-fire, can-never-unsee images of Jamuna’s people breaking rocks in searing heat under that relentless sun, scavenging on mountains of rubbish, charred-brown skin stretched over spindly limbs, children with distended bellies, black hair turned light brown from malnourishment, barefoot for life, not knowing their birthdays or how old they are, and so much else that so seared my mind, splintered my heart and flooded my throat with sorrow that I was dumbfounded in the truest sense, struck mute for a long half-minute.

Thanks for reading. Part Five will explore the realities of casteism in America and hopefully tie everything together.

If you found any value in what you’ve read, please hit that heart button.

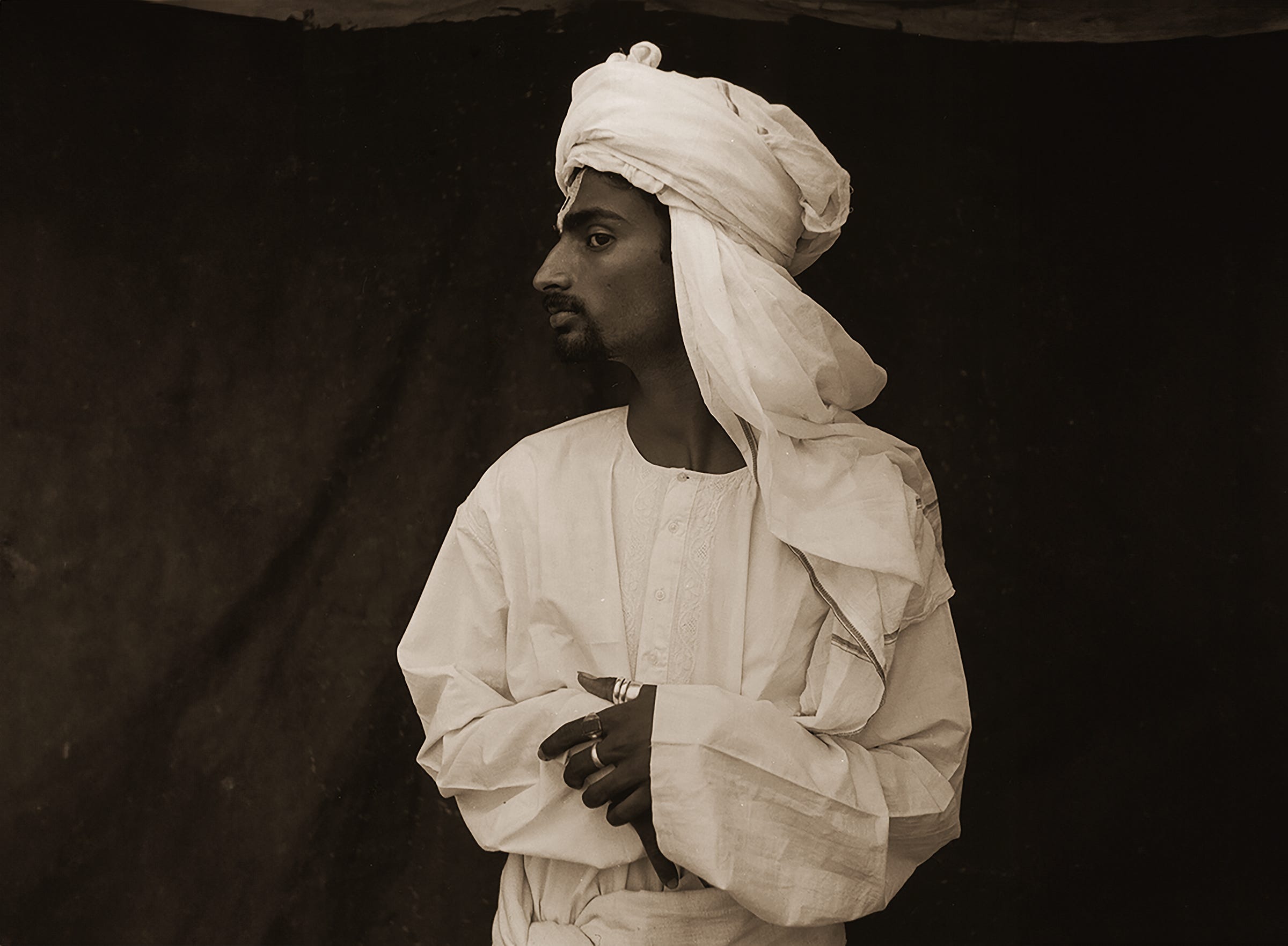

* Regarding the lead image: I helped lug that stone jali behind Usha Rani, the immensely lovable aunt of Bapji, Maharaja of Jodhpur, into the makeshift studio at her residence, Ajit Bhawan — I can still feel the strain of its weight. I didn’t add her caste to the caption per usual: she’s a Rajput Kshatriya, the warrior caste from Rajasthan and the rest of the Rajput Belt — my term — across North India.

I extended the backgrounds in her portrait and Mohan Kumar’s using AI to fit Substack’s preference for landscape images.

“Giving liberates the soul of the giver.” — Maya Angelou

Or support this project by acquiring something tangible at my concept store:

FURTHER READING:

Tunku Varadarajan’s review of Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents (free link):

Read full story —>

My article about the Dom Raja and the burning ghats of Varanasi (free link):

Read full story —>

A Quillette article from earlier this year explains how damaging the reinforcement of narratives about discrimination that are largely no longer valid can be.